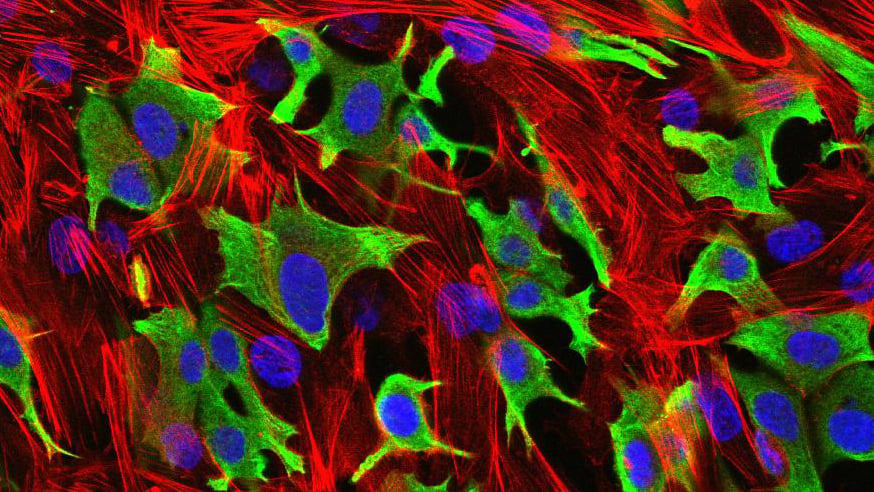

Breast cancer cells (green) invading through a layer of fibroblasts (red). (Luke Henry / the ICR, 2009)

Scientists funded by Breast Cancer Now have discovered a highly promising new approach for treating triple negative breast cancer – blocking a newly identified ‘addiction gene’.

The gene, called KIFC1, was one of 37 new genes that the researchers found triple-negative breast cancers were addicted to, each one of which could be a potential new drug target.

Scientists at Breast Cancer Now’s research unit at King’s College London and their dedicated research centre at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, found that blocking these genes could slow tumour growth but had little effect on healthy cells – paving the way for the development of long-awaited targeted treatments for thousands of patients.

In particular, the scientists validated the KIFC1 gene, also known as HSET, as a drug target for patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Their landmark findings were published today in Nature Communications.

Triple negative breast cancer

Around 15% of all breast cancers are ‘triple negative’, with around 7,500 women in the UK being diagnosed each year. More common among younger women, and also among black women, triple negative breast cancers can be highly aggressive.

They are more likely to spread to another part of the body where they become incurable, and unfortunately still have no targeted treatments.

‘Triple negative’ means that they lack the three molecules routinely used to guide treatment for breast cancers; the oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).

Triple negative breast cancers therefore cannot be treated with targeted drugs commonly used to interfere with these receptors, with patients being limited primarily to surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Research at the ICR is underpinned by generous contributions from our supporters. Find out more about how you can contribute to our mission to make the discoveries to defeat cancer.

Read more

Tumour growth suppressed

In a new study, researchers performed a genome analysis of 182 patient breast cancer samples, to identify the genes either most overactive or present in the greatest numbers that triple negative breast cancers are particularly dependent on.

They then narrowed these down to focus on the genes which were known to be associated with features likely to drive tumour growth and progression.

Having found 130 potential ‘driver’ genes, the scientists – led by Professor Andrew Tutt at King’s College London and the ICR, and Professor Spiros Linardopolous at the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR – performed knockdown experiments to test how lacking these genes affected tumour cells’ and healthy cells’ survival.

They discovered 37 ‘addiction genes’ which, when silenced, suppressed tumour cells’ growth but had no effect on normal cells.

KIFC1 is key

One of the most promising genes for new drug discovery was KIFC1 – a gene involved in helping cancer cells to divide their DNA equally into two daughter cells at mitosis.

In lab-grown cells and mouse models, scientists found that silencing KIFC1 had no effect on healthy cells, but selectively killed tumour cells containing extra centrosomes – the scaffold structures that cells rely on during cell division.

The findings strongly suggest that this ‘centrosome amplification’, a common trait of triple negative breast cancers, depends on KIFC1 for successful cell division.

Following this work, the researchers are looking to discover drugs to block KIFC1 in the hope of creating a targeted therapy for triple negative breast cancers.

Exposing cancer's weaknesses

Study leader Professor Andrew Tutt, Director of the Breast Cancer Now Toby Robins Research Centre at the ICR and Director of the Breast Cancer Now Research Unit at King’s College London, said:

“Our study has exposed a whole series of new genetic weaknesses in triple negative breast cancer – a particularly aggressive form of the disease.

We believe these new ‘addiction genes’ can be exploited to find potentially exciting targeted forms of treatment.

“We studied one of the genes, KIFC1, in more detail, and showed that it could be a particularly promising new target for cancer drugs.

We’re now starting an exciting new drug discovery programme to test the possible benefits of blocking KIFC1 in triple negative breast cancer – with the aim of taking a new class of drug into clinical trials.”

A chink in the armour

Baroness Delyth Morgan, Chief Executive of Breast Cancer Now which funded the study, said:

“Patients diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer unfortunately remain limited to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and surgery because there are currently no targeted treatments available. This can be extremely gruelling, so we desperately need to find them new options.

“These incredibly exciting findings could give us 37 new avenues of hope for thousands of women.

“The term ‘triple negative’ relates to the fact that this type of cancer can’t be treated with targeted drugs commonly used in other forms of the disease. When a woman is diagnosed, those particular words must sound very discouraging, at a time when she is looking for hope and promising treatment options.

“We hope that findings like these will bring us closer to treating this type of breast cancer, so we can redefine it - maybe even rename it – so that patients can feel more optimistic about their future.

“If we could develop drugs to block these ‘addiction genes’ to kill triple negative cancer cells, while leaving healthy cells unscathed, this could be the chink in the armour we’ve long been searching for.”

Louise's breast cancer story

Louise, 38 from Saddleworth, was diagnosed with stage 2, grade 3 triple negative breast cancer in September 2014 when she was just 34 and a fit, healthy working mum with a six year old daughter. Louise underwent six months of aggressive chemotherapy, followed by a single mastectomy.

“For me research is everything, so when I was diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer I immediately began trying to find answers to all of the questions I had about the type of cancer I had, but what I found was terrifying.

“It felt like a death sentence and throughout my treatment I kept thinking I wished I’d been diagnosed with a different type, something that I could feel less frightened of, something that there was a targeted treatment for.

“My treatment was tough; the chemotherapy really took its toll on me and I really struggled to cope. But, if, in the future, we can bring some clarity to explain what triple negative breast cancer actually is, and what it isn’t, this could give hope to the women diagnosed in years to come.

“We need to show that triple negative is not the beast that people paint it to be and it isn’t a lost cause.

“The news that researchers have discovered new genes that could help develop more targeted treatments for triple negative breast cancer is encouraging, and it's great to hear that this field of work is being treated as a priority.

“Today, I’m doing really well, I'm a happy mum to our two amazing young daughters, and my partner and I are also busy planning our wedding. There is light at the end of the tunnel, there is hope, there is life after triple negative breast cancer.”

Breast Cancer Now thanks Walk the Walk for their very generous support towards this work.