US President Barack Obama delivers the State of the Union Address in 2015 (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza / CC BY 3.0)

US President Barack Obama’s recent State of the Union address to the US Congress threw down the gauntlet of curing cancer ‘once and for all’.

As this was backed by the promise of substantial extra funds to the National Cancer Institute, it was more than vacuous political rhetoric.

Its aspiration was redolent of the title of his book – ‘The Audacity of Hope’ – and very American in style: gung-ho; can do; let’s fix it. Which I applaud.

We have of course had a presidentially inspired ‘war on cancer’ before, so a legitimate question is: what’s different now and what are the realistic prospects for a ‘once and for all’ cure?

The challenge is certainly formidable. There has been enormous progress over recent years in our biological understanding of cancer, in treatment and in curative outcomes for some cancers – but some obvious difficulties remain.

Amongst these is the rising incidence of cancer in ageing populations; the cost of treatment within tax-funded public health care; and the extraordinary diversity of cancer itself and its innate character of cellular resilience to challenge.

The word ‘cure’ appeals to an expectant public but it is perhaps somewhat misleading – even more so reference to ‘a cure’. This feeds expectation of a quick fix or a pill for all cancers or, yet again, a magic bullet. It ain’t gonna happen.

Curing or thwarting?

I would rather pose the question: how can we best control cancer and greatly reduce its burden on society? There is, in my view, no serious prospect for achieving this without recognising, accommodating and exploiting the complex, inherent biology of the disease. The last few years have been a wake-up call in this respect.

The fundamental problem now appears to be, firstly, the remarkable diversity of cancers between patients and within an individual cancer, and secondly the evolutionary character of cancer which generates weed-like robustness, resilience to drug therapy and resistance.

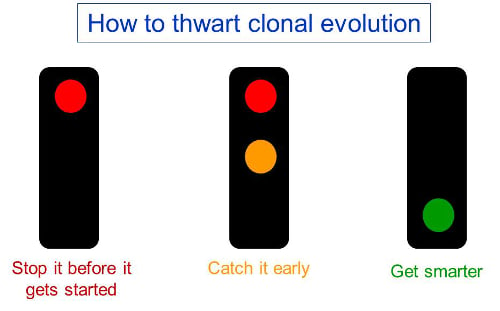

In light of this, the challenge of defeating or ‘curing’ cancer can be re-phrased as: how can we best thwart the evolutionary resilience of cancer? This is more than semantics. The way you pose the question influences the tactics you are likely to adopt.

My opinion on the best overall solution for this concurs with the stated strategic vision of some of the biggest cancer research organisations internationally, including the National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research UK – though we may not all agree on the apportioning of effort and resources and the potential benefit of the different components.

We are in a race against evolutionary progression that fosters resilience.

So, the best strategies would seem to be: stop it before it gets started; catch it early; or, if that’s not possible, then come up with more efficacious therapies that avoid drug resistance. It’s not rocket science, is it? And I think it’s a no-brainer that all three of these strategies will be required.

Anyone disagree?

Preventable disease

It’s not too dissimilar from the longstanding challenge of controlling infectious pathogens that rapidly evolve resilience to therapy.

Does anyone think we got on top of the common lethal infections more with antibiotics than with vaccines or better sanitation?

If you had malaria, you might well benefit from the very efficacious anti-malaria drug artemisinin (barring the emergence of drug resistance). But you would be well advised, in a malaria region, to use a mosquito net.

Cancer Research UK declared that some 40% of cancers in the UK have currently avoidable causes. I believe this underestimates the potential fraction of preventable cases.

Some 35 years ago, Richard Doll and Richard Peto suggested 75% or so of cancers were potentially preventable; other epidemiologists have suggested 90%.

Scrutiny of the worldwide variation in incidence rates of all the major adult cancers suggests that some 75-90% are lifestyle-associated (or dependent) and hence potentially avoidable. Some 90% or so of lung cancers, skin cancers, liver cancers and cervical cancers are probably avoidable.

Getting to grips with the obesity epidemic and modification of calorie intake/use would bring many health benefits, including having an impact on a significant fraction – perhaps one third – of cancer risk.

'Fixable'

There are huge challenges here, some of them logistical, social and economic. But it’s possible.

Breast cancer is especially interesting in this context – an oestrogen-fuelled mismatch between evolutionary adaptive reproductive (and dietary) programmes and modern lifestyles. It ought to be fixable.

As cancers progress and diversify and become more robust, the probability of both metastatic spread and drug resistance increases. The argument for early intervention is therefore unassailable.

It is not without difficulties however. The majority of early lesions that we can detect by surveillance are evolutionary dead-ends and don’t merit intervention, particularly if this is invasive or with significant collateral damage. We very badly need more accurate biomarkers of malignant potential to identify the bad players.

Predicting evolutionary trajectories is possible in simpler, bacterial systems and it could be possible for cancer. Evolutionary parameters may be key.

Genomic diversity, stem cell burden and the diversity of ecosystem selective pressures are variables that should have an impact on the likelihood of progression. It’s not random chance.

Here at The Institute of Cancer Research, a major focus is on the discovery of new, more targeted drugs and scheduling that maximise the chance of avoiding drug resistance and minimise toxicity.

Modelling essential

Our partners the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, as a tertiary referral centre, tend to see more advanced cancers.

For these, improved combinatorial drug (and immunotherapy) treatments offer the best prospect for improved outcome especially for the more malignant cancers that present ‘late’ in their evolutionary trajectories, such as with pancreatic, ovarian, lung and glioblastoma cancers.

This will, for sure, be tricky, not least because of the extraordinary genetic diversity and epigenetic plasticity of cancer clones.

The objective and clear intention is cure – a permanent fix. But the fall-back position should this fail might be to stall or slow down evolutionary progression. For some patients, particularly the more elderly, this would be something of a victory or effective ‘cure’.

Testing many possible drug combinations in varying schedules directly in patients looks impractical. What is called for is some preclinical evolutionary modelling of drug resistance.

In simpler bacterial systems, it has been possible to steer or redirect evolutionary trajectories with respect to drug resistance towards more benign outcomes. Plans are afoot at the ICR – through my colleagues Dr Andrea Sottoriva and Dr Udai Banerji – to adapt this experimental tactic for cancer cells. It could pay rich dividends.

The ICR’s plans to bring together, in one new building, our research efforts in drug discovery and evolutionary biology will facilitate these new endeavours.

So, the big question remains: is Obama naïve or over-optimistic to believe that cancer can be fixed? Anyone who disagrees with that hope and ambition probably shouldn’t be involved in cancer research and treatment.

Certainly more money via the National Cancer Institute or Cancer Research UK’s Grand Challenge scheme should make a difference.

It’s foolish to make precise predictions about the future (other than that it will happen). But we can hazard a guess or speculate on what is possible. Science is always full of surprises, so who knows.

My best bet is that, if all three strategies I’ve described were systematically and vigorously applied, then the total burden of cancer could be reduced by around 90% in 15-20 years. It is audacious, but – any other offers?

comments powered by