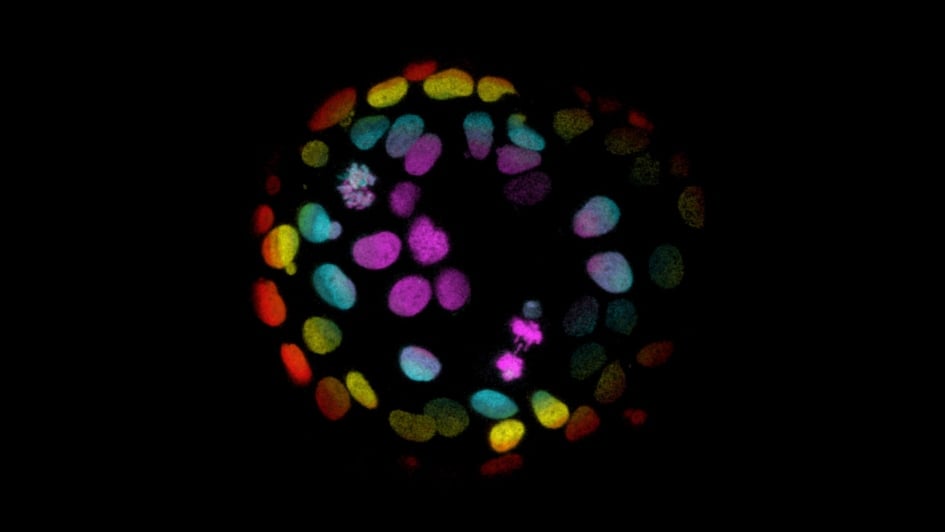

Image: Microscopic image of colorectal cells grown into organoids. Credit: Hubrecht Organoid Technology

Last week I had the opportunity to attend the virtual 2021 National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) conference, where world-leading researchers and healthcare professionals gathered to share details of their contributions to cancer research.

New to this year’s conference were the debate sessions, where experts from around the globe came together to discuss issues central to the future direction of cancer treatment.

Are avatars the future of cancer treatment?

The first debate session, “This House believes every patient should have an avatar to inform best treatment response”, saw a panel of experts discuss the feasibility of introducing a tailored treatment plan for all cancer patients.

An avatar in a clinical context is a surrogate for the patient – a mimic of the patient’s cancer that can be tested for its response to a variety of drugs to determine the most effective treatment plan.

Professor Thomas Helleday, of the Karolinska Institutet, presented how researchers can use tissues grown from tumour biopsies, which are unique to the patient to study individual cancers. These tissues, known as organoids, can be tested with a variety of available drugs to determine the best treatment plan for patients on an individual basis.

This methodology is also being pursued here at the ICR to improve patient treatment. Professor Nicola Valeri, Team Leader in Molecular Pathology, describes our work on organoids: “We are trying to find the best way to predict how and if a patient will benefit from a certain treatment, so by obtaining this little piece of material and growing it in the lab, we aim to find drugs that are going to work for that patient.”

The speakers, including Dr Kristopher Frese from the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute and Dr Bristi Basu from the University of Cambridge, discussed the limitations of avatar-based approaches, highlighting the issue with organoids and other pre-clinical models is their inability to account for all aspects relevant to drug response. While organoids replicate the tumour of the patient, they cannot account for the role of the immune system or the body’s vascular architecture.

Professor Sarah Blagden, from the University of Oxford, presented a significant and unsurprising drawback of this personalised approach to cancer treatment – the cost. The infrastructure and personnel required to execute an avatar-informed response for all patients is astronomical, and this is something we cannot afford in the current climate.

So if avatars aren’t ready for widespread use, where would their application be most beneficial? The speakers agreed that in the case of rare cancers, where large clinical trials are difficult to implement, a patient avatar would be invaluable.

While there are undoubtedly roadblocks to the successful implementation of an avatar system for all patients, the technology itself is promising and represents a step forward towards the future of cancer treatment.

In their closing remarks, each speaker identified the need for cross-institution and cross-discipline cohesion. To them, this is central to the development of more personal treatment plans for cancer patients.

Why do clinical trials fail?

In the final debate session of NCRI 2021, Professor Rob Bristow of the University of Manchester chaired the discussion “This House believes that frequent failure of stratified medicine trials is due to a lack of understanding of fundamental biology”.

The fundamental biology referred to in this case is the study of how drugs impact individual targets in cancer cells, and any experiments which give quantitative scientific data. Understanding how drugs work, and how the genetics of a patient may impact the effectiveness of certain drugs, is critical to designing clinical trials which are both beneficial for the patients involved and the cancer research community.

Dr Simon Boulton, from the Francis Crick Institute, and Professor Alan D’Andrea, from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, spoke about the current tools available for the study of tumours and potential cancer drugs, and how important understanding the basic biology of new cancer drugs is to the design of appropriate trials.

The ICR has long been dedicated to ensuring basic science feeds into trials and back again. Our researchers also pioneered the Pharmacological Audit Trail, which allows researchers to focus scarce resources on the most promising therapies. The Pharmacological Audit Trail provides a gold-standard framework for evidence-based decision-making during drug discovery and development, by using biomarkers to track the effectiveness of cancer drugs.

The approach aims to allow better decision-making to spare patients the side-effects of treatments that will ultimately not help them, and gives a truer picture of the effectiveness of a therapy in those patients it is designed to help.

On the clinical side of the discussion, Professor Gary Middleton of the University of Birmingham emphasised the pressure that clinicians are under to run trials and improve patient care. He suggested that the rush to trial drugs can lead to the critical biological facts being overlooked. Having the time to step back and examine all the fundamental knowledge about a drug, he explained, would stop many of these failed trials from going ahead.

Professor Ruth Plummer from the Northern Institute for Cancer Research at Newcastle University summarised the debate succinctly, acknowledging that the failure of trials is “a bit more complicated than that”. This was reflected by the audience response, who voted against the motion at the end of the session by a steep margin.

At the ICR, we are working to influence policy so that we can harness advances in science to bring innovative drugs to people with cancer as quickly as possible. Our 2018 report on drug access, and 2019 Cancer Drug Manifesto, describe how lighter-touch regulation, more focus on innovation and a drive to develop drugs for cancers of high unmet need and especially for children, will bring benefit to patients quicker.

In 2020 we brought the sector together to create a nine point plan looking at practical recommendations to improve access to new cancer treatments. Earlier this month, the ICR’s Professor Nick James addressed a Parliamentary inquiry on cancer services, highlighting how clinical trial design during the pandemic built on existing cancer trial designs optimised to bring new treatments to patients as quickly as possible – and also emphasising that cancer research could now in turn benefit from processes adopted during the pandemic.

A more coordinated approach to cancer research and treatment

A common theme through both debates was the emphasis placed upon effective collaborations and connections, paving the way for a more coordinated approach to cancer research and treatment.

The ICR is proud to support the team science approach to research, and its ability to bring together different ideas, skill sets and expertise. Through our partnership with The Royal Marsden and close collaboration with other world-leading institutions across the UK, we seek to make critical breakthroughs in cancer research by working together.

It was evident from the debate sessions at this year’s conference that researchers and clinicians are passionate about working together to ensure cancer patients get the best possible care.

The National Cancer Research (NCRI) Cancer Conference is the UK's largest meeting of cancer researchers and doctors.

Read our other blog posts from the event

comments powered by