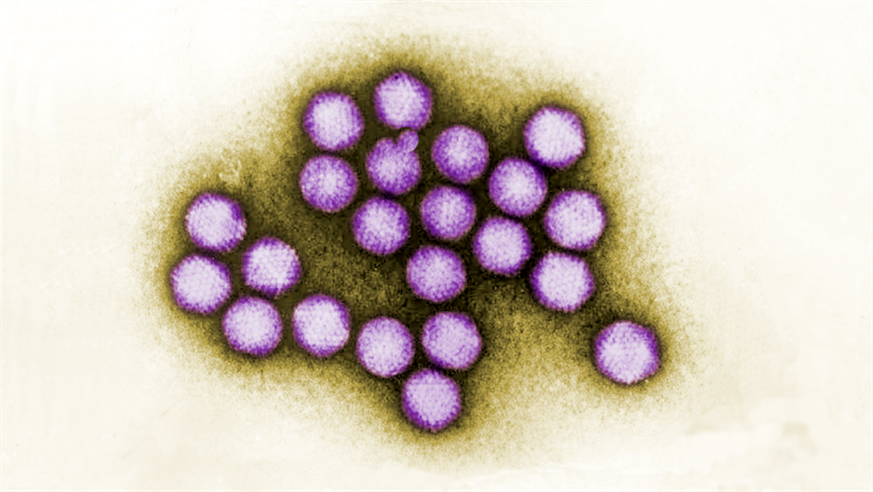

Digitally-colourised transmission electron microscopic (TEM) image of a small cluster of adenovirus virions. Source: CDC/ Dr. G. William Gary, Jr.

There are various hallmarks of cancer cells that allow them to thrive. These can include increased rates of cell division, the ability to ignore triggers that would normally cause cell death, and the ability to hide from our immune systems.

Although these features provide selective advantages to cancer cells, they also enable researchers to distinguish them from normal, healthy tissue – and that can be exploited in cancer treatments.

At the 2018 National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) annual conference, I heard about the discovery of some new and exciting cancer therapies from our own Professor Ian Collins here at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, Dr Allan Jordan from the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute, and Professor John Bell from the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

Stopping cancer cell repair

Most chemotherapies work by damaging the DNA of rapidly dividing cells. But in response, cancer cells activate a molecule called CHK1, which delays cell division and gives cancer cells time to repair the genetic damage. Researchers have been trying to work out how best to target CHK1 and prevent cancers from resisting treatment.

Professor Ian Collins and his team at the ICR have worked to better understand the molecular mechanisms underpinning CHK1 activity.

They have discovered a drug, currently known only by the code CCT245737, which can be used to block CHK1. The drug prevents cancer cells from being able to repair the damage caused by chemotherapy. Clinical trials are now under way to assess CCT245737 both in combination with the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine and as a single agent at higher doses.

Multidisciplinary working is crucial for the success of any cancer drug discovery project, and the team have knitted together research involving chemical and structural biology as they have taken the drug through the design stage towards the clinic.

Professor Collins stressed the importance of understanding how a drug will be used in a clinical setting, so its benefit can be maximised and side-effects minimised.

Catch up with all the latest ICR blog posts and video content from the 2018 National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) conference 2018 in Glasgow.

Read more

Disrupting the way genes are turned on and off

The activity of genes is regulated in various ways and one of them is via ‘epigenetics’, in which DNA is chemically modified to turn off certain genes.

Epigenetics can play a role in cancer, for instance through the silencing of genes that would otherwise suppress tumour growth.

Dr Allan Jordan from the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute has been looking into ways this silencing, or methylation, can be reversed. He is creating inhibitors of DNMTs – the family of enzymes responsible for regulating and maintaining methylation.

This has been difficult because our understanding of how DNMT inhibitors work is limited. He felt it would be worth it, however, as DNMTs present an obvious yet untapped target for new drugs.

Dr Jordan’s closing remarks stressed the importance of a collaborative approach to these challenges, particularly highlighting partnerships between chemists and biologists as being invaluable in developing a preclinical candidate for DNMT inhibition.

Infecting cancer with a virus

The biology that makes cancer cells so adept at survival is the same biology that also makes them vulnerable to viral infection.

Healthy cells have a range of molecular processes in place that allow them to detect, and then fight, viruses. These include instigating cell death, raising an immune response and stopping blood vessel formation (to prevent the virus travelling). Cancers often switch off these processes in order to thrive, and that rather helpfully could make them genetically predisposed to infection.

Professor John Bell from the University of Ottawa is working to understand how they can enlist modified viruses in the battle against cancer.

He explained how the genetic diversity of tumours often thwarts viral therapy as a standalone agent – since cancer cells are able to draw on mutations to develop resistance to treatment.

Instead, he said if we’re to find a cure it is likely to be a combination of different therapies working together. This will naturally have financial implications for our health services, and so researchers are looking to combine these in a cost-effective way.

Professor Bell and his team have developed a therapeutic virus ‘platform’ using a virus that can infect and kill cancer cells, without harming healthy tissue.

Not only this, the modified virus also delivers additional therapeutic benefits at the same time. For example, the virus can stimulate an immune response from the host, acting almost like an immunotherapy, and it can be equipped with additional genes capable of triggering cancer cell destruction.

Collaboration is key

One thing that resonated with me through all of these talks was that cancer research is not an isolated task. In this session alone, I heard references to chemistry, biology, immunology, virology and clinical care.

It highlights the importance of networks and collaborations and the role they play in this work, both internally, through setting up multidisciplinary teams such as those at the ICR, and with collaborations between organisations.

The ICR is proud to support the team science approach to research, and its ability to bring together different ideas, skill sets and expertise. This ethos, and opportunities for scientists to share research ideas at conferences like the NCRI, are so important for us to get essential new breakthrough treatments to patients as fast as we can.

To keep updated on the conference, follow @ICR_London and #NCRI2018 on Twitter for all the latest.

comments powered by