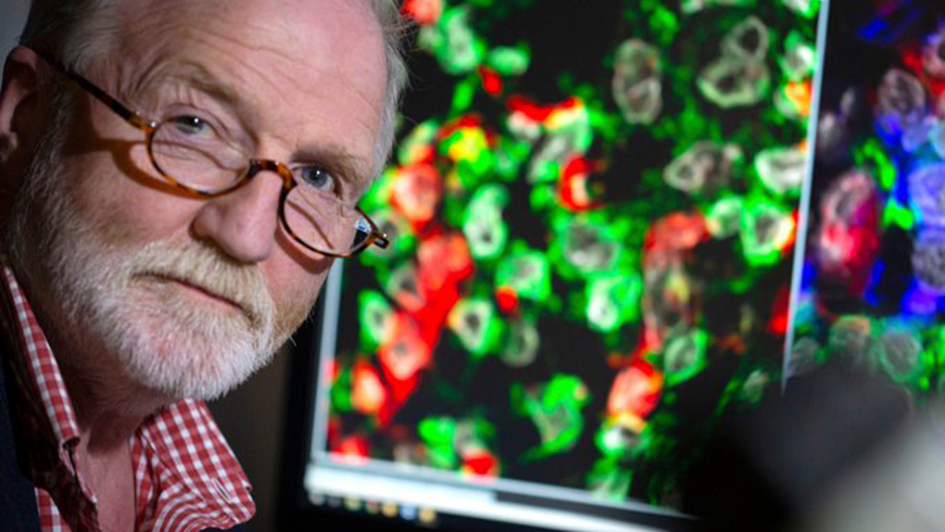

Image: George alongside fluorescent images from his own tumour, showing the cell’s membrane proteins and their metastatic potential

Researchers who study fundamental principles in biology rarely have the opportunity to work with patients. Even if their work relates to diseases like cancer, much of their time will be spent at a bench in a lab working on molecules and cells they can’t actually see.

But at the beginning of the year we were contacted by a documentary maker who wanted to do something a bit different. They wanted to really unpick the science behind the disease, behind the discoveries that led to the latest game-changing treatments and the research that will become the treatments of the future.

The documentary’s presenter, Dr George McGavin, is himself a scientist and was diagnosed with a rare and deadly form of melanoma last year.

The entomologist-turned-TV personality wanted to film something that captured his personal, emotional journey through diagnosis and treatment, but also explore what it means genetically, biologically and medically to have melanoma.

Explaining how melanoma develops

George and the production team came to visit the ICR to find out about our research into melanoma’s ability to spread and the interactions with the immune system.

Following their initial visit, ICR scientists Professor Chris Bakal and David Mansfield worked together to prepare a sample of George’s tumour for imaging so that they could explain on screen how melanoma develops and spreads in the context of George’s own situation.

Below are some of the resulting images and footage from this work. If you want to see who else George met on his journey, then make sure you tune into BBC Four at 9pm on Monday 24 June, or catch up later on BBC iPlayer.

Watch BBC iPlayer clip

Professor Bakal used a silicon maze that he developed in collaboration with a team at Cornell University in the US, showing George how melanoma cells squeeze through tiny spaces to spread around the body.

Cancer’s ability to evolve and change shape is a key step before the disease is able to spread around the body and become deadly.

Professor Bakal’s work in this area could lead to the discovery of new drugs that block cancer from shape-shifting and stop the disease becoming deadly.

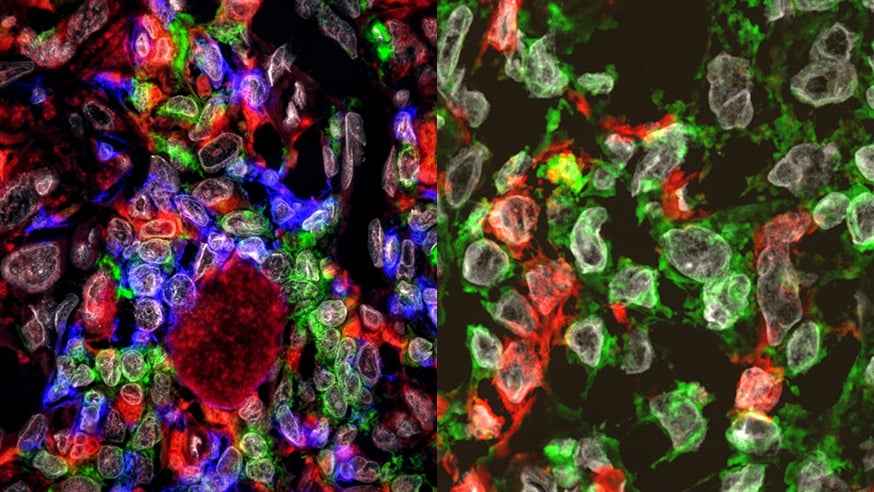

Professor Bakal also used fluorescent imaging (images above) to look in detail at cancer cells (in green) and in particular at their membranes – the outer layer of the cell.

The cells with ‘ruffly’ or more dynamic membranes are more likely to be ready to spread around the body.

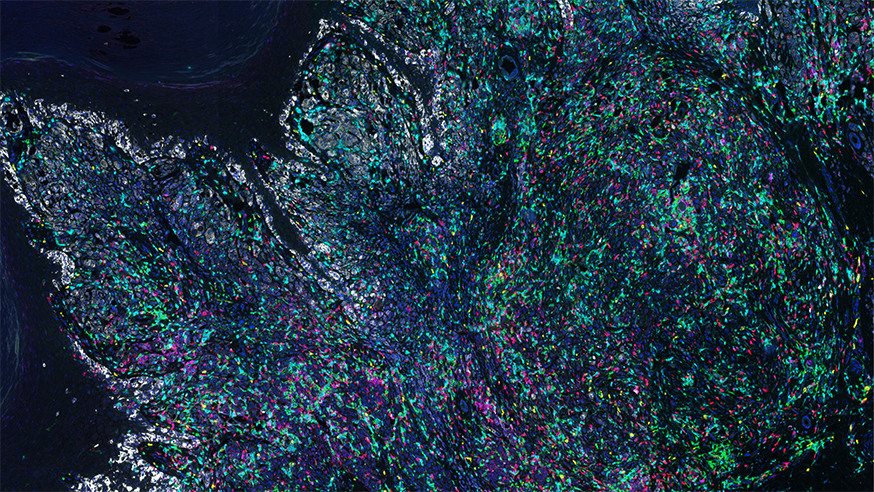

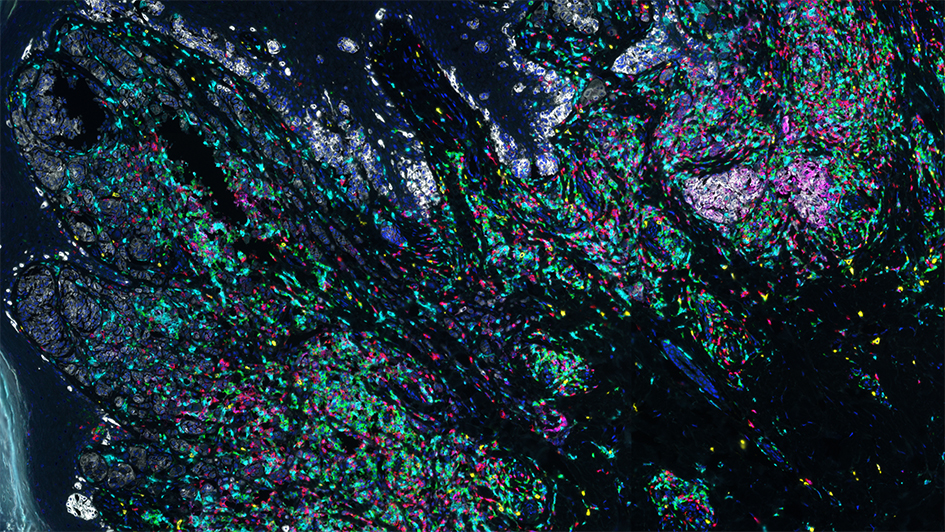

David Mansfield stained George’s tumour (see picture above and below) so George could see the different types of cells of his immune system interacting with his tumour.

The immune system plays a key role in controlling cancer. The latest melanoma treatments called immune checkpoint inhibitors work by turning the brakes off of the immune system so that immune cells are able to attack the cancer and keep it in check.

If George was ever to relapse, these immunotherapies could be one of his next treatment options.

Both images above (by David Mansfield) were taken on a state-of-the-art Vectra 3.0 microscope

David Mansfield, Higher Scientific Officer at the ICR, said:

“I’ve been looking at the immune cells in tumours like this for a few years and am always fascinated to learn just how different the immune reaction to tumours can in different patients.

“This is first time I’ve been able to meet the patient and explain what I can see happening in their tumour. George was thrilled to get such a detailed view of the battle that his immune cells were fighting against his tumour.”

comments powered by