Academic researchers, pharmaceutical representatives and investors come from very different worlds, and there aren’t that many opportunities for them to mix and to learn from each other in a really synergistic way.

That’s a shame, because it’s precisely that mix of scientific inventiveness, state-of-the-art resources and financial clout that is so essential in turning discoveries into new treatments for patients.

So Professor Paul Workman, our Chief Executive here at The Institute of Cancer Research in London, was keen to fill the gap with a different kind of conference that would provide an opportunity for researchers, biotech and pharmaceutical companies – together with charity funders and investors – to share ideas and build relationships.

Professor Workman co-hosted that event – called Horizons in Cancer Drug Discovery – in Edinburgh earlier this month, as it brought together some of the leading figures from academia, the pharmaceutical industry and venture capital.

It was an event that presented important scientific breakthroughs in the context of how they could help drive forward the discovery and development of cancer drugs – and what they could end up delivering for patients. The conference also featured a panel discussion on drug discovery and team science and just as importantly offered numerous networking opportunities.

'Drugging the cancer genome'

Professor Workman opened the event himself with a lively and challenging talk on ‘Drugging the cancer genome’. He highlighted the enormous potential of exploiting the explosion of knowledge about cancer genomes and cancer biology and described the problem within the cancer drug discovery and development ‘ecosystem’ which he explained was not functioning optimally – and may even be delivering “less than the sum of the parts, rather than more” .

Paul set the challenge for the various communities – academic scientists and clinicians, those working in small and large companies and non-profit and for-profit funders – to work together in a more effective way. And he called for more sustainable funding models because discovery and clinical development takes time. He especially highlighted the huge challenge to overcome the evolution of cancers to drug resistant forms in order to extend long-term survival and achieve more cancer cures.

Deciding precisely which drug targets to commit efforts against remains difficult and high-risk, Paul explained. But large-scale genomic profiling projects and systematic analysis of genes involved in cancer progression and resistance is now aiding the critical decisions on how we should approach drugging cancer genomes in the future.

And he emphasized the importance of clever drug combinations adapted to the changing biology of a cancer over time to keep resistance at bay. Paul also talked about his enthusiasm to find ‘network drugs’ that attack cancers at multiple vulnerable points – and he showed how his work on discovering and using HSP90 molecular chaperone inhibitors might be first step towards such a goal.

One of the big themes of the conference was how researchers could find ways of improving the odds of success for drug discovery and development, by picking out the most promising molecules early on, and making sure new clinical trials test them in those patients in whom they are most likely to work.

'Altering the phenotype'

Amongst several other ICR speakers, Professor Julian Blagg, Deputy Director of the Cancer Research UK Cancer Therapeutics Unit, discussed the pros and cons of a strategy called phenotypic screening. This approach can be used in drug discovery to identify small molecules that alter the phenotype – an observable characteristic or trait, such as morphology, development, biochemical pathways or physiological properties – of cells or organisms. He used the example of the WNT pathway, which is involved in tissue development in embryos and tissue maintenance in adults, but when permanently switched on can result in cancer.

Professor Blagg told me: “At ICR we have already successfully used a cell-based phenotypic screening approach to identify small molecule modulators that block the WNT signalling pathway in a specific manner. We are now collaborating with the company Merck Serono to further progress this work.”

'Improving the odds'

Professor Johann de Bono, Professor of Experimental Cancer Medicine at the ICR and an honorary consultant at The Royal Marsden, spoke about ‘Improving the odds with rational clinical drug development’. He discussed how embedding into early clinical trials high-tech approaches such as next-generation genome sequencing and transcriptome analysis – which determines when, where and how much genes are turned on or off – can help greatly with selecting which molecular targeted drug is the best for each individual patient and how to deal with drug resistance.

Professor de Bono argued that by doing this we can now quickly and affordably stratify patients into groups who are more or less likely to respond to particular drugs, improving the chances that clinical trials will be successful and that drugs will be approved for widespread clinical use.

The work of Professor de Bono’s team on clinical trials with antihormonal drugs in prostate cancer – such as abiraterone – and also on PARP inhibitors such as olaparib to exploit the discovery of ‘synthetic lethality’ to kill BRCA mutant cancer cells – provided great examples of progress made.

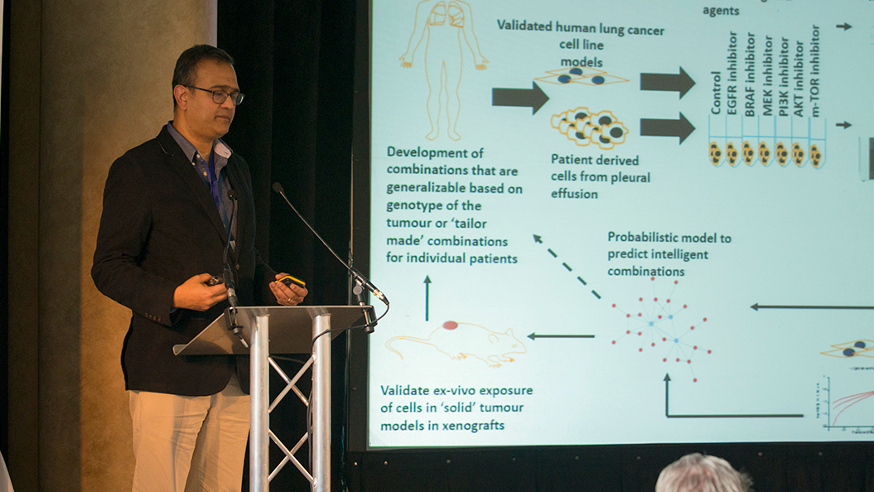

Dr Udai Banerji, Leader of the Clinical Pharmacology and Trials Team at the ICR and an honorary consultant at The Royal Marsden, gave a talk on how new classes of targeted cancer drugs could be combined together to reduce the risk of drug resistance. I caught up with him after the event to find out how the meeting had gone. He was enthusiastic: “This was an absolutely fantastic opportunity for academics, biotechnology and venture capital financiers, and also big pharmaceutical companies to discuss current bottlenecks in cancer drug development. It is becoming obvious that no one sector alone can cover all aspects of drug discovery and development in a sustainable way, and we have to work together for the sake of cancer patients.’’

Professor Paul Workman rounded off the conference with a rousing call to action. He emphasized that great progress has been made in basic cancer research and targeted therapy. But it was essential, he said, to continue the good work started at this event, and for the attendees to make their voices heard in the debate over how to enhance the drug discovery ecosystem – so that it functions more effectively and sutainably. His final word was the need for a strong sense of optimism and also urgency, saying: “Patients are waiting.”

The hope is that by bringing together the different worlds of science, pharmaceutical development and investment, events such as this one can play a significant role in delivering a new generation of cancer treatments for patients.

comments powered by