Image: Darwin finch on branch. Sources: Flickr. Licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license

At The Institute of Cancer Research, London, our researchers are working hard to understand how cancer develops so that we can find new ways to treat the disease.

Cancer cells evolve and adapt to best suit their environment, and the process by which they do this is exactly the same as how animals evolved from a common ancestor into the diverse array of species we see in the world today.

World famous evolutionary biologists, and husband and wife team, Professors Peter and Rosemary Grant from Princeton University delivered a special lecture at the ICR about their life’s work studying evolutionary changes to bird populations on the Galápagos Islands, and what it can teach us about cancer.

The couple were awarded a Royal Medal from the Royal Society in 2017 for their achievements, alongside the ICR’s Professor Mel Greaves, and with this year’s medal winners having just being announced, it’s fitting to look back at their outstanding research.

Darwin's Finches

The Grant’s have been visiting Galápagos since 1973 to study Darwin’s Finches, species of birds which are found nowhere else in the world. Their research gives a fascinating insight into evolutionary theories developed by Sir Charles Darwin nearly 200 years earlier.

Darwin famously visited Galápagos in the 19th century where he encountered the finches of Galápagos as well as other animals.

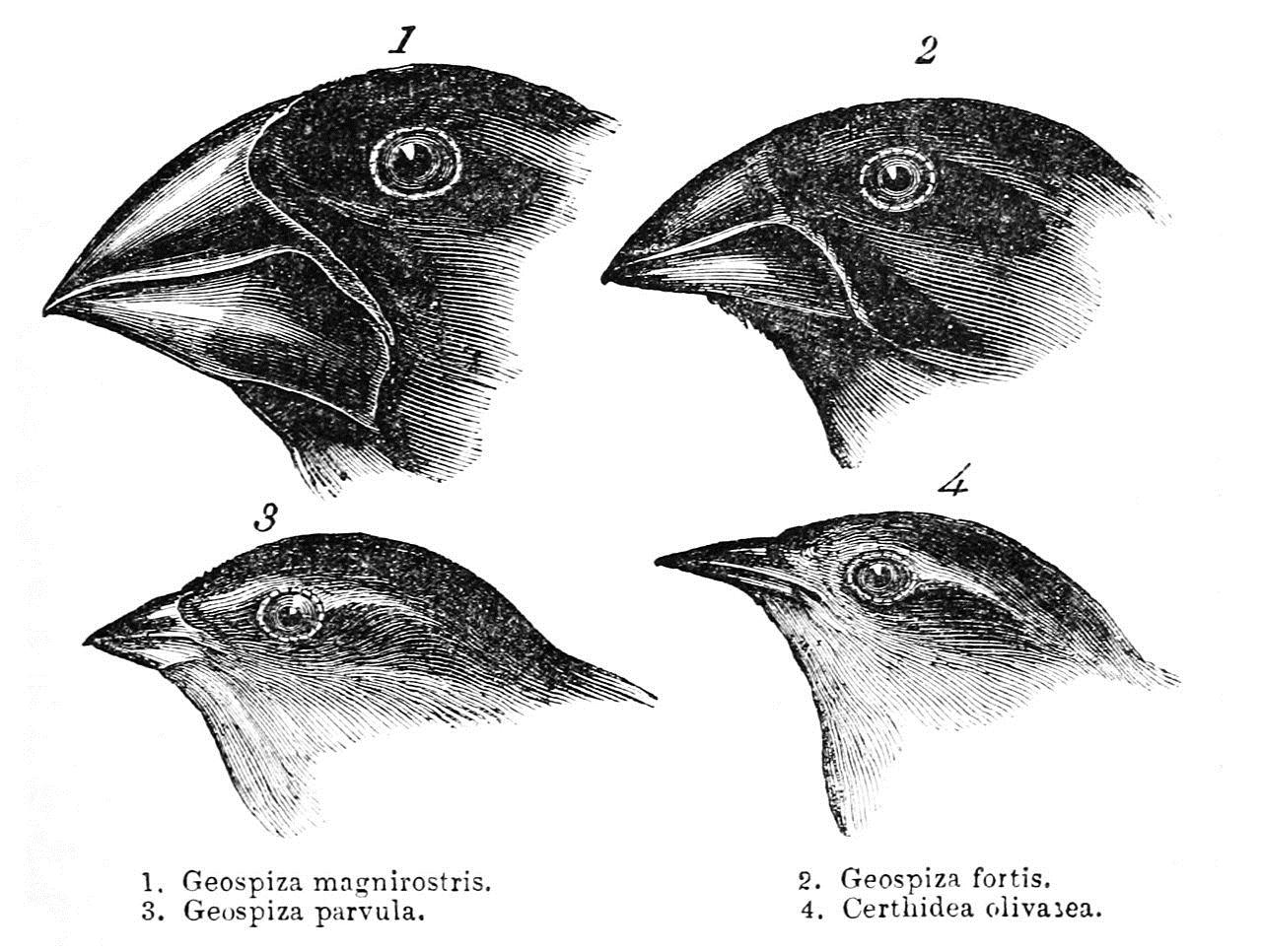

Image: Darwin's finches or Galapagos finches. By John Gould, 1845. Source: Wikimedia Commons (CC0)

He noticed each island seemed to have their own populations of bird, and although they looked similar, the size and shape of their beaks varied significantly from island to island.

His studies led researchers to understand that there were distinct species of finches unique to each island, specially adapted to the conditions found there to help them survive.

Drawing from these observations Darwin proposed his theory of evolution, where species change over time through a process called natural selection.

Donate towards the Centre for Evolution and Cancer to help fund the brightest minds in the field to set up new research teams, and to provide studentships and fellowships for the development of new talent.

Find out more

Evolution through natural selection

All living organisms are made up of genetic material which dictates the characteristics the organism displays, with variations in those characteristics happening through reproduction or through random mutations.

Some genetic variations lead to benign changes in characteristics, like eye-colour in humans, but others can have an impact on how well that organism is equipped to survive in its environment.

If a genetic variation produces a characteristic which benefits that animal, it is more likely to survive long enough to reproduce and the characteristic gets passed on.

Equally, changes that hurt an animal’s survival chances are less likely to be passed on, so over time the more advantageous trait becomes more common. It’s why some animals have patterned fur to blend into their environment, and why albino animals are rare, because they are easy to hunt.

On Galápagos, beak size and shape were examples of traits that could help birds eat seeds found on the islands, so Darwin’s Finches evolved differently shaped beaks through natural selection to become better adapted to feed on the seeds specific to each island.

Darwin assumed it would take thousands, if not millions of years for natural selection to change animal populations to the extent that distinct species would form, but the finches on Galápagos show that new species can occur much more quickly.

Evolution in real time

For Professors Rosemary and Peter Grant, the Galápagos Island Daphne Major was the ideal place to study evolution in action in the local bird populations.

It’s so isolated that it has never been inhabited by humans, so any changes they found between species would be down to natural selection.

The Grants studied the birds on the island over decades, and their painstaking work demonstrated very rapid changes in body and beak size in response to changes in the food supply were driven by natural selection.

They saw three significant shifts in rainfall which changed the seeds available to finches on the island, causing some populations to die off, while giving others more suited to the new conditions a survival advantage.

In periods of drought larger, stronger beaks helped the finches to break tougher seeds when their normal food supplies became scarce. But in extended rainy seasons when food was plentiful, these traits were not nearly as useful, so the Grants saw that beak sizes from one generation to the next would begin to shrink.

Their research uncovered genetic markers linked to the size and shape of beaks of different species of finch that helps the populations adapt to better suit their environment.

By taking genetic samples from the birds they saw that beak size has gone both up and down across species of birds on the island over time illustrating that evolution is always happening

If Darwin were alive today, he would surely have loved to have found not just examples of evolution in action, but also the biological mechanisms behind them.

New ‘Big Bird’ species

And over years of visiting the island, the Professors also saw a new genetically distinct population of finch develop, which occurred after interbreeding between a migrant male and females native to the island.

They nicknamed this hybrid species ‘Big Bird’, as it was larger than the native species, with a differently shaped beak, allowing it to exploit different food sources on the island.

The Grants were incredibly lucky to have been present at the rise of a brand new species, but their research shows that interbreeding between similar species could have occurred many times throughout history.

The new lineage of birds developed on the island in just two generations and could one day develop into a completely new and distinct species of bird, showing that evolution can occur rapidly in the right conditions.

So what about cancer?

Professors Peter and Rosemary Grant’s work is a fascinating story, but their work has important lessons for cancer research too.

In many ways the tissues that make up our bodies are very similar to the ecosystems on the islands of Galápagos, as they are both constantly changing. Like the finches of Galápagos, cancer cells are subjected to natural selection and competition that change how they develop over time.

Cancer cells are in a battle for survival against themselves and their environment, and the speed which cells divide means random mutations that provide a survival advantage can spread incredibly quickly.

Natural selection gives cancer the tools it needs to evolve and adapt, which is why it’s so hard to treat, but the ICR’s Centre for Evolution and Cancer is applying these principles to help us understand why we develop cancer and more effective ways to treat it.

The Centre brings together computational biologists, geneticists, cell biologists and clinical scientists to explore exciting new avenues of cancer research based on evolutionary biology.

They are working hard to identify the diverse genetic populations of cells that make up an individual’s cancer, and exploring ways to genetically profile tumours to predict how the disease may progress in the future.

If our scientists want to find new treatments for cancer and prevent cancer cells from developing resistance then they need to understand how evolution works in nature, so they can beat cancer at its own game.

comments powered by