Photo: Jan Chlebik for the ICR 2011

One hundred years ago, Paul Ehrlich, the founder of chemotherapy, dreamt of creating 'magic bullets' for use in the fight against human diseases. His vision inspired generations of scientists to attempt to create powerful cancer-seeking missiles.

Now, antibody-drug conjugates – or ADCs for short – could be delivering that dream.

Dr Udai Banerji – Reader in Molecular Cancer Pharmacology at The Institute of Cancer Research, London – has recently written a review with Nikolaos Diamantis from The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust on the philosophy underlying ADCs and current research developments.

I caught up with Dr Banerji to hear more about ADCs and what the future holds for these drugs.

What are antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)?

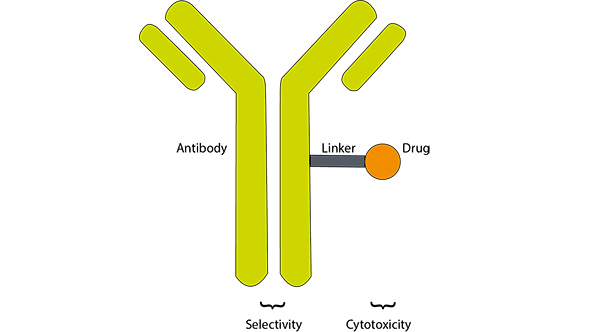

By combining an antibody with chemotherapy, an ADC has the selectivity of a targeted treatment but adds cytotoxic – cell killing – action. Acting like a GPS system, the antibody guides the drug to tumour-specific antigens on the surface of cancer cells. The antibody then binds to the surface antigens, allowing the ADC to be taken into the cell where the chemotherapy is released to kill the cell.

This is a diagram of an antibody-drug conjugate. The antibody is associated with a specific substance on a tumour and can bind to its shape like a lock and key. The cytotoxic agent is designed to kill target cells when it becomes internalised by the tumour and released. The linker attaches the cytotoxic agent to the antibody and needs to be stable enough to only release the agent when inside the targeted cells.

What is the current ADC landscape?

First generation ADCs had limited success, but years of research has led to refinement of these complex drugs. Dr Banerji told me that two ADCs have now been licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration – brentuximab vedotin and T-DM1 – and they are already establishing their place in cancer treatment. Combination strategies with these drugs are being actively explored in many ongoing clinical trials.

There is also a multinational trial – the UK centre being led by the ICR and The Royal Marsden – which is investigating an ADC called SYD985 in patients with advanced solid tumours.

Dr Banerji has already seen exciting results with this drug that target the HER-2 protein, which is over-expressed in certain tumours, such as breast and stomach cancers. The trial is currently still optimising the dose and schedule of the drug which can be given safely to patients, but preclinical studies have shown excellent anti-tumour activity in HER2-positive models.

What does the future hold?

Honing the process of selecting patients who are most likely to respond to ADCs is a continuing effort. Researchers want to move away from selection techniques that require tissue biopsy and use non-invasive methods like circulating tumour cells, predictive biomarkers or imaging techniques. Specific tests that measure the amount of target antigen are already being considered.

Researchers are also testing alternatives to the antibody components of ADCs. High-affinity molecules, like folic acid, or small antibody fragments are all current contenders.

Dr Banerji explained that using these alternatives could deliver the drug more effectively than antibodies do, resulting in better anti-tumour activity. However, there would be trade-offs, which could include a higher drug metabolism so a larger dose would be required.

Progress is already being made, though, and new ways of binding the antibody with the drug, coupled with more powerful cytotoxic payloads, are already leading to more stable and effective ADCs.

Paul Ehrlich's ideal of ‘aiming precisely’ using drugs with high efficacy is still dominating modern drug discovery. It will certainly be interesting to see whether ADCs will become the magic bullets against cancer in the future.

comments powered by