They say that in this world nothing is certain except death and taxes. The famous phrase highlights that there are aspects of life that are simply unavoidable – taxes are the price of living in a society, and death is the inevitable cost of growing old.

They say that in this world nothing is certain except death and taxes. The famous phrase highlights that there are aspects of life that are simply unavoidable – taxes are the price of living in a society, and death is the inevitable cost of growing old.

Although cancer can strike at any age, as you grow older the likelihood of developing cancer during your life also grows, so it too becomes increasingly unavoidable with age.

Cancer and evolution have the same underlying cause – random mutations in the genetic code – but why the process of ageing evolved in cellular organisms in the first place, is a bit of a paradox.

In her talk, Professor Dame Linda Partridge explained how evolution and ageing are intertwined, and how we might find ways to link the way we approach ageing and age-related diseases like cancer in the future.

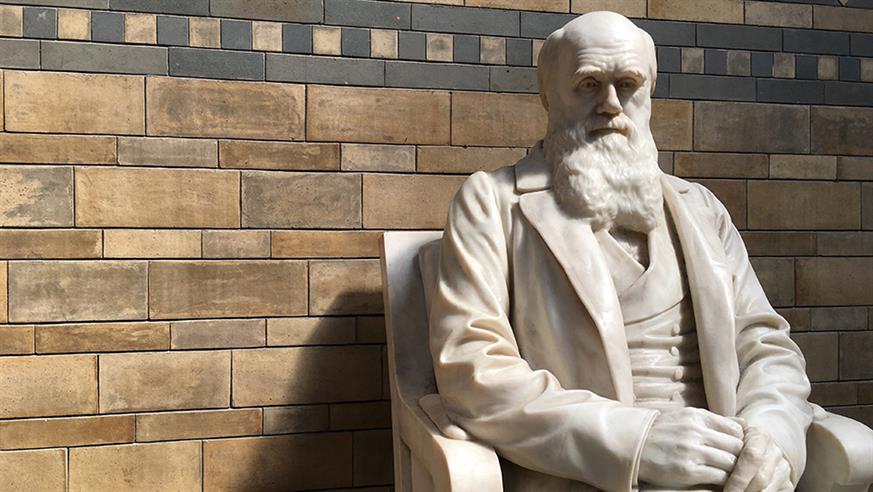

Celebrating Darwin’s birthday

The ICR's Darwin Lecture commemorates the birthday of Sir Charles Darwin, the founding father of evolutionary biology who proposed the theory of evolution by natural selection, which is key to understanding cancer and its development.

Each year Professor Sir Mel Greaves, Director of the ICR's Centre for Evolution and Cancer, invites a special guest from the field of biology and evolution to give the lecture at the ICR.

Professor Dame Linda Partridge is a British geneticist based at University College London (UCL), who studies the biology and genetics of ageing and age-related diseases, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

Her research looks at how healthy lifespans could be extended and the treatments that could keep us in good health for longer as we age.

Ageing and natural selection don’t mix

Dame Linda explained that ageing appears at first to be a particularly odd characteristic to have developed, from the evolutionary point of view.

Sir Charles Darwin spent his life studying how characteristics are passed from one generation of creature to another, but he may never have considered ageing as a process that developed in animals.

Professor Partridge suggested that either it didn’t occur to Darwin to think about it, or if he did, he couldn’t reconcile ageing with his concept of organisms evolving through natural selection.

Darwin’s theory proposed that organisms evolve through incremental changes, that we now know are caused by random mutations in their genes, giving them survival benefits in their environment.

When they reproduce they pass their genetic information on to their children, and the beneficial characteristics are passed on too.

Over time animals become uniquely adapted to their environments, giving rise to all of the diversity of life we see around us. But when animals age their bodies start to fail, so there is no survival benefit to ageing.

During ageing creatures are more likely to die and are less able to reproduce, so their ability to contribute to the next generation is impaired. So how did the process of ageing evolve?

By-product of natural selection

Professor Partridge explained that there must be something else happening to cause ageing to develop, and there are two main reasons: adaptations that benefit the young at the expense of the old, and the fading impact of natural selection as we get older.

If organisms don’t survive long enough to reproduce, any unique traits they have will be lost, so natural selection will favour changes that benefit the young.

But once an animal has reproduced, their death is less likely to prevent the survival of their species, and may actually be beneficial by freeing up resources for the young.

Both of these mean that any negative characteristics caused by mutations that only become apparent later in life will continue to be passed on, particularly if they provide a survival benefit earlier in life, and so we end up with the process of ageing degrading our bodies over time and making us more prone to diseases like cancer later in life.

We are now poised to outsmart cancer with the world’s first anti-evolution 'Darwinian' drug discovery programme, in which we will focus on understanding, anticipating and overcoming cancer evolution, and preventing drug resistance.

Support our work

The hallmarks of ageing

Ageing is therefore a side-effect of natural selection, but it isn’t a given and animals age at very different rates.

Some species of whales live for hundreds of years while smaller mammals like mice live for just a few, but the naked mole rat can live for about 30 years (and almost never gets cancer!), and a species of jellyfish could technically live forever.

Despite these variations, there are characteristics of ageing which occur again and again, and they can also be manipulated.

Professor Partridge shared some examples of drugs that are already being used as treatments which could also reduce the effects of ageing and the onset of age-related disease.

One such drug is trametinib, which is used to treat cancers like skin cancer and lung cancer.

Giving very low doses of trametinib, much lower than would be used to treat cancer, can increase the lifespan of male mice by about 20–30%.

And an immune suppressing drug called rapamycin, which is used to prevent tissue rejection in transplant operations, has also shown good evidence of extending lifespans of mice and preventing the development of tumours in fruit flies.

Embedding Darwinian principles in drug discovery

Professor Partridge’s findings are, for now, still confined to the lab, but these encouraging results show that drugs could play a role in the fight against diseases linked with old age, including cancer.

The Darwin Lecture provides an opportunity to share important evolutionary research with scientists from across the ICR so they can draw upon it in their work against cancer.

Professor Mel Greaves, and his colleagues in the Centre for Evolution and Cancer, will be instrumental to our ‘Darwinian’ drug discovery programme, which aims to tackle cancer’s lethal ability to evolve resistance to treatment. The ICR’s new Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery will be home to that pioneering programme.

By bringing together evolutionary scientists and drug discovery teams under one roof, in the new building, the researchers will be able to collaborate more effectively and further embed evolutionary principles into the ICR’s research to find new and better cancer drug treatments.

Understanding how cancer evolves, and learning how cells evolved mechanisms that cause them to age, is key to finding ways to prevent these processes through drugs, which could help us live healthier lives for longer.

comments powered by