Targeted cancer therapies have been a massive breakthrough in cancer treatment. Our ability to specifically target genetic weaknesses in cancer means that we can focus treatment on the tumour, without harming the patient’s healthy cells.

With this smarter approach we can more effectively treat cancer, with treatments that are much kinder to patients and that cause fewer harmful side effects.

If genetic testing reveals that a patient’s tumour has a specific mutation, that should in theory mean that it would respond to a drug targeting that mutation. But new research led by the ICR’s Professor Udai Banerji, published in Molecular Cancer Therapeutics today, has shown that it’s not that simple.

Different responses to targeted drugs

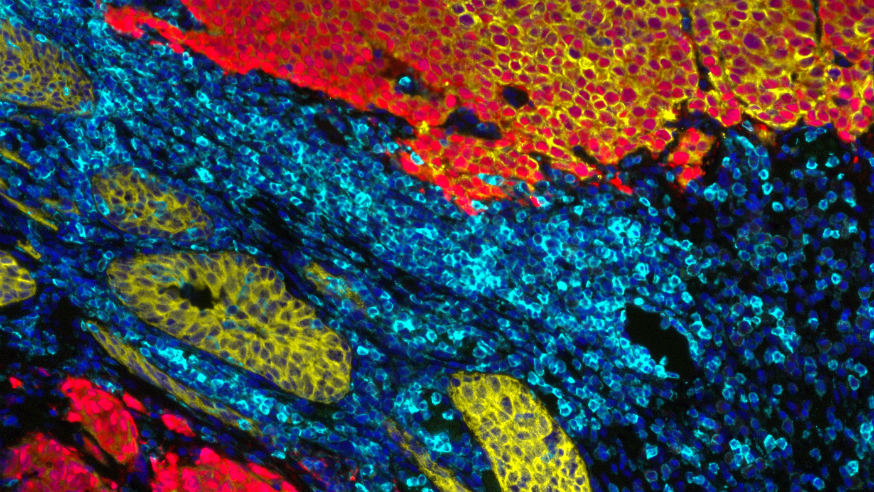

The study found that cells from different organs behave very differently in response to treatment. The chain of signals triggered by targeted drugs varied in cells from either lung, bowel or pancreatic tumours.

This goes against the face of a lot of what we know about precision medicine, but it’s not entirely unexpected. Cells in different tissues have fundamentally different functions and are wired differently from as far back as in the womb, when organs are first formed.

There has been some evidence for different responses to targeted drugs in the clinic already. For example, a class of drugs blocking a gene called BRAF works very well in many patients with melanoma skin cancer, while these drugs have not been successful in bowel cancer.

On the other end of the spectrum, targeted treatments blocking the cancer gene TRK seem to work as a sort of skeleton key. They are effective in tumours with TRK gene faults ranging from childhood soft-tissue sarcomas to bowel cancer in adults.

Implications for precision medicine

Explaining the new research in more detail, Professor Banerji told me, “Our new study is the first to look at ‘dynamic’ signalling patterns, where we analyse the response to targeted drugs in different tumour types. We zoomed in on the chain reaction of molecular switches being flipped in response to targeted drugs.

“We found that drugs blocking the output of common cancer switches, PI3K and MEK, triggered very different chemical signals in lung and bowel cancers.”

These results are interesting in and of themselves, but looking at the bigger picture, they could have much broader implications for the way we think about precision medicine.

“It means that we have hit upon an underlying explanation for the different responses we see in the clinic – and it could allow us to better understand which tumour types are likely to respond to new targeted drugs.” Professor Banerji added.

And looking at the way targeted drugs affect the inner workings of the cell’s response to treatment could also offer important clues about when and how tumours start evolving to evade treatment.

Cutting off cancer's escape routes

This knowledge will serve as important context for the work in the ICR’s planned Centre for Cancer Drug Discovery – where our scientists will be working to predict how cancer will evolve in response to treatment, so its escape routes can be cut off with clever drug combinations to slow or block cancer evolution.

It means we could even revisit targeted drugs that had been deemed to have failed in early stage trials in one form of cancer, to see if they could benefit patients whose tumours stem from a different organ, but have the same genetic fault.

Already, Professor Banerji and others at the ICR have started to take this information into account when designing new clinical trials to test the benefit of new drugs targeting specific gene faults.

We are building a new state-of-the-art drug discovery centre to create more and better drugs for cancer patients.

Find out more

Going forward we need smart clinical trials, looking at the effect of new targeted drugs or combination treatments in the lab alongside the traditional data looking at the number of patients who respond.

Ultimately, this could not only offer a much better picture of the possible benefit of new cancer treatments, it means we can focus on getting new drugs to those patients who stand to benefit the most.

comments powered by