Image: Jo Williams, with her son Lucas. Credit: Jo Williams/Lucas' Legacy

Lucas often used to say, “Tell me about when I was a baby.” So I would say, “You were born on 6 September 2008, at 11 minutes past 11 on the best day of my life. You were 6lbs, one ounce and the most beautiful baby in the whole world....”

Lucas was our only child. He was the centre of our world. He’d never been ill and never had a day off school. He was just really happy and sporty and kind. But then he suddenly started to feel unwell. This was in January 2015.

We’d recently moved house, so we put it down to him feeling a bit unsettled. He’d sometimes lie on the settee for a while, which was not like him, but then half an hour later he’d be running around again. We couldn’t put our finger on what was wrong.

One evening in May 2015, when I came home from work, Lucas was playing football outside when my husband noticed he was holding his arm at an unusual angle. We called Lucas inside and asked what was wrong. He casually said he hadn’t used his arm all day, as he couldn’t hold his pencil properly at school – he’d just decided to use his other hand instead.

We took Lucas to A&E, where they did a CT scan and found what they thought was ‘a cluster of blood vessels’, and they arranged an MRI scan for the following day.

Sat in the ambulance, Lucas still had mud on his knees

It was World Book Day that day, and two of his school teachers came to visit him in hospital: one dressed as Mary Poppins and the other as Mrs Twit. Lucas was sitting up in bed, still in his football kit, chatting away and sorting out his football cards.

And this was also the day that we found out Lucas had a brain tumour.

It was a total shock. I remember not being able to feel my legs when the doctor told us and not being able to stand up. After the scan results, we were taken to Alder Hey Children's Hospital in an ambulance. Lucas sat in the back, chatting all the way to the paramedics and playing ‘I spy’. He really liked them; he loved their uniforms and their badges. I’d never noticed paramedics had such good badges before. Lucas showed them the Space Badge he’d won at Beavers the week before.

Image: Lucas wearing a Bob the Builder hat. Credit: Jo Williams/Lucas' Legacy

Sat in the ambulance, Lucas still had mud on his knees from playing football the day before.

I was terrified, the kind of terror I’d never experienced before. Terror that slowly seeps deep into your bones and decides to settle there, making itself at home.

But I still never believed that Lucas would die.

He was young, he was full of energy, he was fit, he always had his ‘five fruit and veg a day’, and he was so completely loved. I thought this most of the way through our terrible journey. How could Lucas die?

We gradually found out drips of information... Lucas’s tumour was deep in his brain. It was in ‘the clockwork’ of his brain. Lucas’ tumour was inoperable.

But we started chemotherapy, armed with total hope and belief, with what we were told was ‘an aim to cure him, to kill the tumour’. I made the doctors repeat this twice just to check that I’d heard them correctly.

Then, I spent the night on my knees.

In July, we'd completed the chemotherapy, and we triumphantly went for radiotherapy. Lucas had already been measured for his radiotherapy mask and had painted Spiderman on it. He was excited to wear it.

Lucas made a rocket in bed that day. My rocket boy.

But more drips of information: the tumour was ‘behaving’ differently. Lucas had deteriorated. The latest scan ‘wasn’t very good’.

Non-stop questions from Lucas this morning: “Is a dinosaur tooth bigger than a man? What’s inside a dinosaur?”, “Is Crouchie taller than a traffic light?”, “How far is West Brom to West Ham?”. I was constantly on Google to keep up with him.

That’s when the consultant radiologist told us the unthinkable. That Lucas wouldn’t survive.

My Lucas. My boy. My favourite person in the whole world. My heartbeat. My favourite part of me.

I remember saying “but I can’t live without him”. As if that mattered enough to change it.

The only three options were all palliative, all only extending his life for a few weeks, none curing him, none killing it.

Image: Photo montage of Lucas. Credit: Jo Williams/Lucas' Legacy

We aimed for his seventh birthday

So we sat there, with the radiologist and a nurse. We showed them photos of Lucas, running, jumping, laughing. Full of life.

I wanted every decision to be about him and what was best for him. We talked about how amazing he was, how beautiful, how funny, how clever, how kind, how precious. I remember that the radiologist had tears rolling down her cheeks as we talked. We told them that Lucas was waiting for us at home with his Nanna and Grandad. Waiting to know what he had to do next.

Then we decided – the hardest decision of my life – that Lucas shouldn’t spend the last weeks of his life on more horrendous, painful treatments, miles from home. The radiologist asked if there was anything we wanted to aim for, and we said Lucas’ seventh birthday on 6 September.

Can this be my life? Surely I must have stumbled into the wrong place.

Then they took me to another room so that I could scream. It was the loudest and bloodiest of screams. A mother’s siren of despair. A noise I didn’t recognise, from deep within my soul.

I spoke to Lucas in the car on the way home. He said, “Hello Mummy, when will you be home? I’m building Police Lego with Grandad. When do I need to go again?”. I told him that he didn’t need to go again, and he cheered… pause… “But can I still keep my mask?”

I am living someone else’s life: a surreal world of nightmares and fantasy, of screams and cheers, of impending death and Lego.

On autopilot, we organised a birthday party. Lucas planned every single detail, but he became so poorly that we had to bring the party forward to 1 August. It was a final affront to our hopes and dreams, to our promised future.

That night, Lucas left me a note in bed. It said “See you in the morning x”.

Image: Lucas holding an ice cream. Credit: Jo Williams/Lucas' Legacy

In the end, Lucas was too poorly to attend his own party. It was just outside our house, with a bouncy castle, a slide, water pistols and goggles (in case it rained), animals, Punch and Judy, and real sand. It was the party of all parties, with no birthday boy.

Afterwards, Lucas asked me to tell him over and over again all about it: who came, what his friends did, what their favourite things were, who they played with, and he smiled.

Our rollercoaster of desperate hope and extreme despair was almost at an end.

That day, Lucas said, “I think about feeling poorly and I feel sad. I worry about you mostly. I don’t want you to feel bad”.

On Friday 7 August at 4.15am, Lucas died in my arms, at home, in his own bed, just 11 weeks and one day after his diagnosis, and four weeks before his seventh birthday.

I held his little lifeless body tight. As if it mattered enough to change it. I sang to him and stroked his perfect face and hair, and I held his little hand.

I’m so sorry Lucas that I couldn’t protect you. My heart is completely drowned.

Image: Lucas smiling. Credit: Jo Williams/Lucas' Legacy

Can you try harder?

When Lucas was feeling really ill, he’d say he “felt like he was being dragged through a hedge backwards”. When he was having a better day, he’d say he “felt like he was being dragged through a hedge forwards”.

We told Lucas that we were trying to make him better, and he said, “Can you try harder?”

Towards the end, Lucas said “I don’t feel good enough to be alive”. He couldn’t see properly, or walk as well, and then he started not to be able to walk at all. We carried him everywhere he wanted to go. He couldn’t use his right arm, or hear properly, and his headaches were bad.

We would have done anything it took to save our son's life. We would have walked to the end of the earth and given everything we had. I still would. If the treatments could have saved his life, we’d have tried every single one.

But they didn’t help, and some made him feel terrible. I think that Lucas kept going until he just couldn’t anymore.

And Lucas kept us going throughout it all. He was so brave and funny, and he just kept smiling and trying his best.

It is the worst thing I’ve ever gone through, and will ever go through in my lifetime. I have never experienced pain and suffering like this. I didn’t know it was possible. Because Lucas did suffer. I don’t think people always realise that, and it’s why I’m so passionate about funding better treatments for other children. So many beautiful years are lost when a child dies. Along with all your hopes and dreams, your whole future, your reason for living.

Image: Lucas playing football. Credit: Jo Williams/Lucas' Legacy

Seeing what’s been done with Covid-19, and how much can be achieved when money, and effort, and importance, is put behind something – I want us to get back some of those beautiful years for children like Lucas.

We have since set up a charity called Lucas’ Legacy. After Lucas died, we were so devastated to find out how little funding there is for childhood brain tumour research. We just couldn’t believe it. Some of the parents at school had already started to raise money while Lucas was alive, in case we needed to pay for treatment abroad, and we decided to build on that.

‘Lucas’ Legacy’

We always try to do fundraising that’s relevant to Lucas. We’ve done football tournaments and marathons and bike rides. We’ve arranged climbing competitions, triathlons and baking contests. We’ve dressed-up as pirates and superheroes, because Lucas loved them.

The fundraising really helped me in the early days. So many people loved my son. They became part of ‘Team Lucas’, and it just became a movement – we call it ‘LoveNeverEnds’.

Getting money for research is really hard. So far, we’ve raised more than £184,000. £160,000 has gone to support the ICR’s research into childhood brain tumours, and the rest has gone to a local children’s hospice and to Lucas’ school, who have been absolutely amazing throughout.

A huge amount of research has been made possible because of the money we’ve raised, and it means that Professor Chris Jones and his team at the ICR have been able to gain a better understanding of what drives these cancers, and turn this knowledge into potential new treatments.

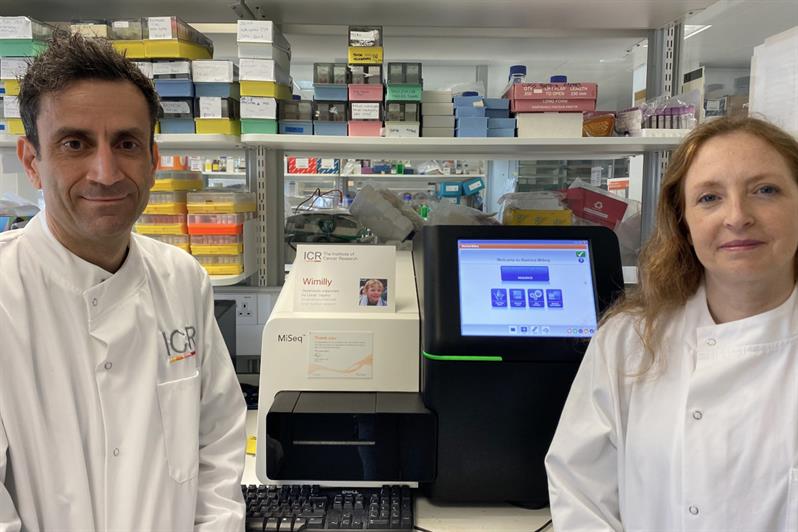

In their lab is a MiSeq machine – a vital piece of equipment which reads the genetic code of tumour samples and is central to much of the work the team undertakes. They have affectionately named it ‘Wimilly’ in honour of Lucas, and the support they’ve received in his name. Lucas used to call us 'The Wimillys' when he was little, before he could say his surname properly. Seeing the machine there in the lab, with Lucas’ beautiful smile keeping it safe, means so much to us.

Image: Professor Chris Jones and Higher Scientific Officer Anna Burford with 'Wimilly'. Credit: The Institute of Cancer Research, London

I said earlier that Lucas kept us going throughout, and he keeps us going now. Lucas didn’t make it to his seventh birthday, but his legacy could mean we help another child to reach theirs.

Learn about the incredible discoveries made by Professor Jones and his team.

Research news from the Glioma team

A journey of courage

When he was ill, Lucas showed me courage that I never even knew existed. True courage, not people doing things they enjoy, or being honoured for doing what they love, but courage that involves real suffering. Facing each day in pain and still smiling, never complaining, always trying his best, never giving up, never saying ‘why me?’.

After Lucas died, I used to walk around a room in my head. It was an empty room with no doors or windows. I used to look for a way out, but there wasn’t one. The room is called Grief.

Grief has become my companion. It is precious to me. I keep it with me. It is my testimony. A physical testimony felt deep inside. It is a testimony of how I love Lucas.

I miss all the little things – that are actually the big things. I miss putting his pyjamas on the radiator and wrapping him in a big fluffy towel. I miss hearing footsteps in the night and him coming into me with an armful of teddies. I miss putting kisses in his hand ‘for later’. I miss squeezing his hand three times, and we both knew it meant, "I love you". I miss his smell and his voice. I miss his beauty. I just miss him.

Six years since losing Lucas, we've adopted a son. We've adopted a little boy who needed a family. He was nearly seven. Nearly-seven is old for adoption. It's the end, not the beginning. It's where nearly everyone has given up on you. It's where nobody is fighting for you, really fighting, like a mum who would give anything, a mum who would walk to the end of the earth for you. Lucas showed me the courage to do it. Without him, I could not have done it.

Just before Lucas died, he said, “I chose you to be my Mama. Everybody wanted you, but I chose you. There was a whole queue around you.”

Image: Lucas runs in his Stoke City football kit. Credit: Jo Williams/Lucas' Legacy

I have two sons: one who has taught me so much about love and courage and loss, and one who is teaching me so much about survival and hope and how to carry on.

LoveNeverEnds

If you would like to make a donation to help find new and more effective treatments in Lucas’ name, you can here: https://www.justgiving.com/lucaslegacy-cbts

comments powered by