Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, with more than 52,000 cases diagnosed in the UK each year.

Over the years, we have seen remarkable breakthroughs in prostate cancer research. From the discovery of the drug abiraterone, now a mainstay of treatment for advanced prostate cancer, to the development of olaparib, the first precision medicine for advanced prostate cancer, and new ways to screen for and diagnose prostate cancer. These discoveries have helped many men with prostate cancer live longer with a better quality of life. You can read more about these advances in ‘The future of prostate cancer research: what could the next decade bring?’ blog post.

However, much more needs to be done to convert our increasing knowledge of prostate cancer into the next generation of innovative treatments. Regional differences in NHS resources, delays in taking drugs through clinical trials and fundamental problems with how cancer drugs are licensed and appraised for use in the NHS means that patients are not always benefiting from these scientific discoveries.

If we are to fully harness the potential of research discoveries and provide all cancer patients access to the most effective treatments as early as possible, changes are desperately needed in the drug discovery and development landscape.

The use of biomarkers in prostate cancer research and treatment

As our understanding of cancer biology increases, we are seeing a shift away from a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach towards a more personalised, targeted approach for cancer treatments. This new era of precision medicine is revolutionising the way in which drugs are developed, enabling treatments to be targeted towards a specific cancer mutation and vulnerability.

Using drugs which target features specific to a person’s cancer means they tend to have fewer side-effects compared to conventional chemotherapy. It also means treatments are more cost-effective for the health system as only patients who are most likely to benefit receive a given treatment.

These new targeted treatments can often be tailored very effectively for individual patients using biomarker tests that indicate to clinicians which patients are most likely to respond to a given drug. Various measures can be used as biomarkers including genetic mutations, proteins produced by tumours or physical and biological changes detected on a scan.

There have been major success stories in targeted drug therapy development including olaparib, a precision medicine best known for its use in breast and ovarian cancer. Results from the recent PROfound trial, led by Professor Johann de Bono at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, have shown that it can also be effective in men with prostate cancer who have tumours with mutations in specific genes involved in DNA damage repair like BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, the latter of which was discovered at the ICR. Routine genetic profiling of patient cancers would allow identification of such mutations and more targeted, effective treatment.

Tests for BRCA1 and BRCA2 are already included on the NHS national genomic testing directory for cancer but provision of these tests is patchy and inequitable across the UK. Additionally, the eligibility criteria for genetic testing are complex and tend to focus on family history of cancer, rather than testing all patients with the disease. This means many people are missing out on the potential for monitoring, screening, or preventive treatment.

The ICR is calling for all cancer patients to have their cancers genetically profiled at diagnosis and during treatment as standard within the NHS. This would allow access to more personalised, effective treatment by identifying those most likely to benefit from a treatment.

Barriers to biomarker testing

Biomarkers have a huge role to play in the future of precision medicine but regulatory processes and resources have not kept pace with scientific advances. This has resulted in several barriers to the routine use of biomarker tests meaning patients are potentially being denied the best treatment option for them.

A major hurdle in accessing biomarker tests is the lack of incentive to invest in biomarker research. Biomarker testing and development is expensive, with the costs of development too often being judged to outweigh the benefits of their use in diagnostic/treatment combinations.

Technology appraisals by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) tend to consider companion tests as an additional cost, which can make treatments appear less cost-effective and so less likely to be recommended for use in the NHS. This can discourage industry and academia from investing in biomarker research. Recent data shows that only 18 per cent of cancer drugs assessed by NICE during 2016-2019 were accompanied by a biomarker test.

However, use of biomarkers could reduce healthcare costs overall by targeting therapies to those who are most likely to respond favourably to the drug, resulting in more efficient and cost-effective treatment.

In addition, using biomarker tests to guide clinical trials will allow selection of patient populations that are more likely to benefit from the drug being tested. This in turn will help generate clear evidence of benefit in these subgroups meaning the trials are more likely to succeed and the treatment more likely to gain marketing approval, reducing the time to patient access.

To fully realise and benefit from the advances in precision medicine, we need biomarker tests to be routinely developed alongside new cancer drugs. This means we need to incentivise companies to bring forward biomarker tests alongside new treatments and for UK appraisal bodies, like NICE, to take a more positive view of companion biomarker tests.

Improving access to prostate cancer treatments

Breakthroughs in prostate cancer research have paved the way for a new generation of state-of-the-art treatments to be developed.

Discoveries like that of Lutetium-177 PSMA - an innovative new therapy used to treat metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer - could be a game-changer for prostate cancer treatment. Lutetium-177 seeks out cancer cells by detecting the presence of a target molecule called prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) on the cancer cells' surface. Once in contact, a high dose of radiation is delivered, destroying the cells.

However, the full potential of these discoveries are missed if patients are unable to access them quickly. All too often, treatments suffer long delays before reaching cancer patients and becoming part of routine care. On average, it can take around 11 years from patent registration to patients being able to access the cancer medicine on the NHS in the UK (The Institute of Cancer Research, 2016).

Improving patient access to innovative cancer drugs could, at least in part, be achieved by generating evidence of a medicine’s safety and efficacy more quickly. To achieve this, we need greater use of innovative trial designs that make use of biomarkers to direct treatments at defined patient populations.

A more flexible approach to licensing could also be beneficial, speeding up the regulatory process. For instance, adopting approaches like adaptive licensing, where regulators assess drugs on early evidence such as progression-free survival or quality of life and then later review their benefits in terms of overall survival, and eventually on real life-use data.

The high prices of modern cancer drugs are another significant barrier to patient access, and change is needed to make drugs affordable to healthcare systems. This could include use of innovative models like outcome-based pricing which ties the price of a drug to the beneficial outcomes it achieves or, allows price to be varied depending on the cancer indication in which it is being used.

The impact on patients

It is critical that patients with cancer have access to innovative drugs and treatments as early as possible. Tony Collier was diagnosed with prostate cancer in May 2017. When he was diagnosed, Tony asked his oncologist whether he could be put on abiraterone through his private medical insurance. He had heard about abiraterone from results presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference in June 2017 but knew it was not readily available in the NHS.

Tony is disappointed that abiraterone is not available as a first-line treatment in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, despite its availability in Scotland and its use to treat more than 500,000 men with advanced prostate cancer worldwide. He said: “I originally had private medical insurance which helped to fund my abiraterone. Unfortunately, the premium on my medical insurance escalated to such an extent that I could no longer afford it.

“Luckily, my oncologist found a way of getting the NHS to fund the drug for me two years ago. So, I've had four years of the drug funded by private medical insurance and I’m currently funded by the NHS. Of course, abiraterone has now gone generic so the cost is a lot lower than it was when I was first diagnosed.

“For some men, abiraterone as a first-line treatment is a complete godsend. We need to make abiraterone available throughout the UK, particularly now that the drug is off patent and therefore much cheaper. People should be able to access the best treatment that's most appropriate for them and their circumstances.”

Improving clinical trial regulation and access

Well-conducted clinical trials are instrumental in taking scientific advances from bench to bedside. They also allow patients access to the newest treatments ahead of their approval. However, clinical trials are also one of the lengthiest stages in the drug development pipeline.

A report published by the ICR (From Patent to Patient), which examined how quickly drugs were getting to patients on the NHS, highlighted that delays in taking drugs through clinical trials and getting them licensed was significantly impacting patient access to treatments. It was found that between 2009 and 2016, the average time taken for a drug to go from phase I trial to European Medicine Agency (EMA) authorisation was 9.1 years.

Hurdles present at each stage of setting up and running clinical trials can significantly slow the process down, creating a need for smarter, more efficient trial designs. A great example of innovative trial design is the STAMPEDE trial led by Professor Nick James and the MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL, which aims to evaluate multiple treatment approaches for people affected by high-risk prostate cancer. STAMPEDE used a multi-arm, multistage trial (MAMS) design to answer multiple questions simultaneously under a single trial protocol rather than using a series of separate studies.

This type of pioneering trial design is more cost effective as it removes the need to set up individual trials and allows more patients to be given novel treatments rather than being on a control arm of the study. New arms can also be added while the study is ongoing, making it more efficient than designing a whole new trial and helping to accelerate the drug development process. The regulatory framework, however, is not yet set up to facilitate MAMS trials, which currently restricts the flexibility of these types of trials.

Unequal trial access and falling recruitment

The ICR has a vision that a suitable trial should be made available for every person with cancer who wants to be part of one, but a series of barriers are preventing this from happening.

Funding for clinical trial research varies substantially across the country, meaning not every patient has equal access and many are missing out on the opportunity to take part in potentially lifesaving research. Also, the excessive administrative burden in setting up clinical trials, especially for innovative trial designs such as biomarker-driven studies for personalised medicines, is delaying access to the latest treatments. This is further exaggerated by the lack of system in place for the NHS to perform rapid genetic testing on patients to select them for targeted treatments.

The Covid-19 pandemic has compounded these longstanding issues with trial funding, regulation, and access. In fact, cancer trial recruitment dropped by 59 per cent during 2020/2021 compared to the three years prior to this. This decline in trial recruitment seen during the pandemic has slowed down the pipeline of new treatments.

We are yet to recover from the impact of Covid-19 on clinical trial recruitment, indeed cancer trial recruitment was still 13 per cent lower in 2021/22 compared to pre-pandemic levels. Much more needs to be done if we are to see a clinical trial being made available for every cancer patient who wants to participate in one.

There are several measures that need to be taken to overcome these barriers, including equalisation of resources to run clinical trials, improved regulation to encourage the use of trials with scientifically innovative designs, such as those driven by biomarkers, and increased integration of clinical research into the patient care pathway from point of diagnosis.

Addressing radiotherapy research and availability

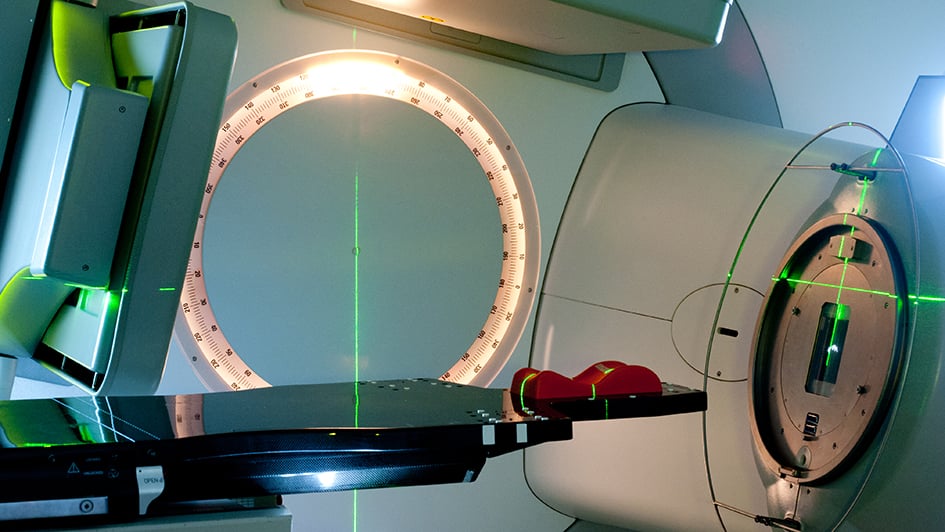

In general, radiotherapy and surgery are considered the most effective treatment options for cancer, with around 30 per cent of prostate cancer patients receiving radiotherapy as their main treatment.

There have also been many advances in the field of radiotherapy including new ways of targeting tumours more precisely, increasing its effectiveness and reducing side effects. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), pioneered at the ICR and The Royal Marsden, is one such approach which has improved outcomes and quality of life for many men with prostate cancer.

In 2023, the PACE-A clinical trial involving Dr Nicholas van As and Professor Emma Hall, showed that advanced prostate cancer patients experience fewer urinary and sexual side effects following a course of advanced radiotherapy called stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) compared to surgery.

SBRT allows clinicians to target tumours to sub-millimetre precision, delivering five high doses of radiation to patients over one to two weeks, compared with standard radiotherapy, which delivers more moderate doses through approximately 20 sessions over four weeks. Improving treatment this way not only reduces the burden on patients having to travel into hospital to receive treatment but can reduce an individual’s treatment time and enable the NHS to treat more patients.

Despite these advances, many prostate cancer patients are still missing out on these potentially life-saving treatments because of under-investment in new radiotherapy technologies and, shortages of trained staff. There is also a lack of support for radiotherapy in clinical trials. This is amplified in certain regions of the country resulting in some patients having to travel long distances to access up-to-date treatments or the latest trials.

We desperately need governments to address this regional variation and invest in upgrading radiotherapy equipment and infrastructure to ensure that patients across the UK have access to the latest, high-precision forms of radiotherapy. Alongside this, we need to make sure healthcare professionals are trained in the latest radiotherapy technologies, allowing clinical practice to keep pace with scientific advances.

The importance of innovation

Prostate cancer survival in the UK has tripled in the last 40 years owing to advances in research. But, as with all cancer types, prostate cancer is a moving target which can evolve dynamically over time and become resistant to treatment. If we are to beat prostate cancer, we need to develop treatments which attack the cancer in brand new ways.

We currently know of at least 500 cancer-causing proteins, but we have drugs to target less than 10 per cent of these. More effort is needed to discover innovative drugs that act on currently untargeted cancer proteins. However, there is a level of risk associated with novel targets which pharmaceutical companies may be unwilling to take on. We need a system which actively encourages creative risk taking if we are to see the development of exciting, novel treatments.

Innovation is not only central at the discovery stage. We need the concept of innovation to be embedded into each stage of a drug or therapy’s journey to market, from early development to clinical trials, right through to licensing and evaluation of cost-effectiveness.

Our understanding of the biology and genetics of prostate cancer has increased rapidly but we are not yet seeing the same progress in the discovery, development, and delivery of new treatments. We need to foster a research ecosystem which supports, incentivises, and rewards innovation at each stage of a treatment’s development pathway. This is the only way we will be able to deliver step-change improvements in prostate cancer outcomes.

comments powered by