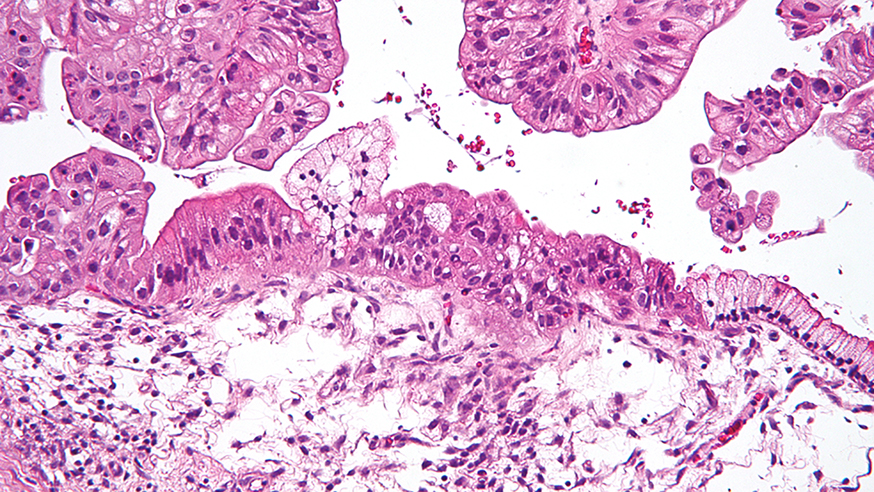

Intermediate magnification micrograph of a low malignant potential (LMP) mucinous ovarian tumour. Image credit: Copyright © 2009 Michael Bonert. Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0.

Women with advanced ovarian cancer who begin treatment with olaparib are more likely to respond to the drug if it has been more than a year since their last round of chemotherapy, according to new research.

The study suggests that the length of time between finishing platinum-based chemotherapy and starting olaparib could help to predict which patients will have the best response to the drug.

The research was led by researchers from the Drug Development Unit at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust.

It looked at patient records from 108 women with an inherited mutation in their BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, and who had been treated with olaparib for advanced ovarian cancer. All the women had been treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

The researchers found a response in 42 per cent of women whose last chemotherapy treatment ended more than a year before they started on olaparib.

This compared with 18 per cent of patients whose chemotherapy ended less than a year before they began olaparib treatment.

There was also a higher response rate to olaparib among women whose cancer responded to previous platinum-based chemotherapy: 35 per cent, compared with 13 per cent of women whose disease was resistant to the treatment.

The research was published in the journal Oncotarget.

Precision medicine

Olaparib was the first cancer drug to be approved that is directed against an inherited genetic mutation, and its discovery and development were underpinned by research carried out by scientists at the ICR.

The drug targets cancers with faulty BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, which play a key role in repairing DNA damage. ICR researchers Professor Alan Ashworth, Professor Andrew Tutt and Dr Chris Lord found that using drugs called PARP inhibitors causes breaks in DNA that BRCA-defective tumours struggle to repair. This causes the cancerous cells to die, while sparing healthy cells.

We identified the breast cancer gene BRCA2, enabling families with a history of breast cancer to be assessed for future risk, and laying the groundwork for developing novel forms of therapy.

However, some patients with ovarian cancers with faulty BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes still do not respond to the drug. Being able to predict in advance who will benefit from the drug could allow potential non-responders to be given an alternative treatment more quickly.

Dr Yap, who worked in the Drug Development Unit before moving to take up a position at MD Anderson Cancer Center, said: “The recent approval of olaparib heralded a new era of precision medicine in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, but improved strategies for selecting patients who will benefit the most are urgently required.”

“We have shown that the time between platinum-based chemotherapy and olaparib treatment could potentially be an important factor to consider when treating future patients with the disease.”