My son, Ollie, was such a cheeky chappy. I remember at his first school disco, he came up to me and kissed his girlfriend right there in front of me. He must have been in Reception class at the time.

He was constantly up to something, and always joking. He was so full of life, and he loved everything: he loved his friends, he loved school, he loved water. He had this kind of aura – this amazing presence – about him.

Towards the end of November, in 2011, Ollie would say he had a dizzy head and veer off into the wall. Or he’d bend down to put his shoes on, and he’d fall over.

Ollie was always playing jokes, so you never quite knew when to believe him. I wasn’t sure if something was wrong, or if he was just messing around.

But then I’d watch him go to school, and he’d veer off to the left. I knew something wasn’t quite right, and I still hoped it was just in my head, but we took him to the doctors to make sure.

Over the next 10 days, we went to the doctors three times. In the meantime, I kept Googling his symptoms to see what could be wrong. At the third visit, I insisted he go to the hospital to get checked out.

I remember that day because it was 1 December, which was the day of Ollie’s school play. Ollie was playing Joseph, and in the days leading up to the play, he’d had to have assistance on stage because he couldn’t stand up on his own.

‘I needed something to happen’

Within a matter of hours of being at the hospital, we had to sit with Ollie on the bed because he couldn’t sit up on his own. The doctors got him to walk, and I remember thinking – I don’t know quite what I was thinking to be honest…

I needed something to happen, but I don’t know what. I almost wanted them to find that something was wrong, because then they could make it better. But I didn’t want anything to be wrong.

Image: Ollie in school uniform. Credit: Sarah Simpson/Ollie Young Foundation.

They did a CT scan, and within a couple of hours they told us Ollie had a brain tumour. They said they needed to do further tests at the John Radcliffe hospital.

That’s all we knew until we got to the hospital, but I think my instant reaction was ‘okay, that’s fine, we can deal with this’.

Ollie had a friend in his class at the time who had a brain tumour, and he’d had treatment after treatment after treatment, and he seemed to be fine, so I think for me that meant Ollie would be fine too. I thought ‘we’re going to get through this – we can manage it’.

I went into mummy mode. I wanted to keep things as normal as possible, so I made sure Ollie still said his pleases and his thank yous, and ate his dinner nicely, and those sorts of things. And I tried to make sure we were having as much fun as possible.

The next morning, Ollie had to go for a biopsy. There was an issue, because his tumour was in his brainstem, so if he had an operation, it was likely he wouldn’t come out of it.

Ollie’s father, Simon, and I were in limbo. Did we do tests, and could we save him? If we didn’t do the tests, what would happen?

We signed a form to say we were happy for him to go under. The waiting was painful. I think he was under for about four or five hours.

It was amazing when he came round, because he’d woken up and he just wanted to eat. And we thought this is great, because this is Ollie, and he loved his food. And he was eating, and he was happy.

He was given two weeks to live

But it went downhill again, because we got the results – which said that Ollie had the worst brain tumour there could be: a grade 4 glioblastoma.

And he’d be lucky if he had two weeks to live.

That was when it started to hit home. At that point, they also said to us there was nothing more they could do, and they recommended a hospice for end-of-life care.

Ollie stayed in the hospital for a week, and then we moved to Helen & Douglas House hospice. It was the best decision we ever made. As soon as we walked in, it was just like he was home. They offered him a plate of peanuts and crisps, while we had a cup of tea and had to sort a few things out, and he just seemed like a different child. He was happy, and he was settled.

Ollie made so many friends during his time there, and he couldn’t do anything wrong – he had them wrapped around his finger.

Image: Ollie playing with water. Credit: Sarah Simpson/Ollie Young Foundation.

The staff took really good care of him, and nothing was ever a problem. Ollie went swimming every day, and they’d let him take control of the shower – whoever was in there at that time would get soaked. I said it before, but Ollie really loved water. His grandad had a pool, so he’d always enjoyed going in that, and if he got hold of a hosepipe, it would be over his head, or he’d be splashing everyone in the bath.

The next few weeks were spent going back and forth between the hospice and home. There were times when Ollie was better, and we could manage his symptoms at home, but we’d have to go back to the hospice again. We did manage to spend Christmas at home, but then he was back at Helen & Douglas House on Boxing Day.

We bought Ollie a go-kart that Christmas. He was in a wheelchair at this point, but he didn’t like it, and he didn’t want to be outside much. I don’t think he minded being different, but I think in his head he knew he could do things, like walk, that he physically couldn’t do anymore, and I don’t think he liked that.

Ollie loved the go-kart though. Although he couldn’t pedal, he could steer with one hand, so we would hold him up while pushing him along. It was really lovely to see him like that.

Image: Ollie with his brother, Jamie. Credit: Sarah Simpson/Ollie Young Foundation.

We managed to bring Ollie home one more time after Christmas. It was the middle of January, and he had a surprise visit from One Direction, who were his favourite band. They came to sing his favourite song, What Makes you Beautiful, and, unfortunately, Ollie managed to stay awake until the moment they got there, and then he fell asleep.

Ollie’s love of life kept him going

I think, subconsciously, he could hear what was going on though, because he would move and flutter his eyelids. And, as soon as they left, he woke up again.

Ollie was one of those people who didn’t like fuss. He loved attention and making people happy, but he didn’t want the attention all on himself. So maybe that was why he did that. I don’t know. But that was an amazing day.

But then a few days later, Ollie wasn’t well, and we were back in the hospice, and that was where we spent the last six weeks.

Twelve weeks and three days is how long Ollie held on for. He was such a fighter. I think it was his personality, and his love of life, that kept him going for as long as possible.

We’d planned to have people over to the hospice for his birthday on 27 February. We asked him if he wanted a party, but he couldn’t talk to us. He could barely open his eyes at this point, so we didn’t get much out of him. I think I knew he didn’t want it to happen, so we decided just to have a few people over in the end.

I told Ollie this, but that night, he went really downhill. I don’t think he wanted people around when he couldn’t join in himself. He would love to be the soul of the party and enjoy it. Maybe that was his time to go – maybe he’d had enough.

And that was it.

We never told Ollie he had a brain tumour. We’d told him initially that something in his head was making him poorly, and that the doctors were trying to work out what it was. We never told him he wouldn’t survive, but I think, deep down, he knew.

‘It’s okay to let go’

I remember Simon having a conversation with him once, on his level, about how much he knew and what was going on. And I remember Simon saying to him ‘it’s okay to let go’.

As his mum, I don’t think I could have had that conversation. I think I just needed to make sure that he was happy, that he was safe, and that we were caring for him.

The Ollie Young Foundation came about because, after Ollie’s death, we were having a conversation with a friend, and we asked if there was something we could do to raise money to fund research into brain tumours.

There were a couple of weeks between Ollie’s passing and the funeral, and I would go to the funeral parlour and sit with him, because I didn’t want him to be on his own. And then after the funeral, reality set in, and I thought ‘what do I do now?’.

And I decided I couldn’t just sit there and carry on as normal, because something had to be done. If someone could have done something years ago, then maybe we wouldn’t have been in this position.

So I rang up my friend, and said ‘right, this is what I want to do – can you help me?’. That night, I sat down and drew the Ollie Young Foundation logo with his initials, and we contacted a few friends, and asked if they’d like to help, and it hasn’t stopped since.

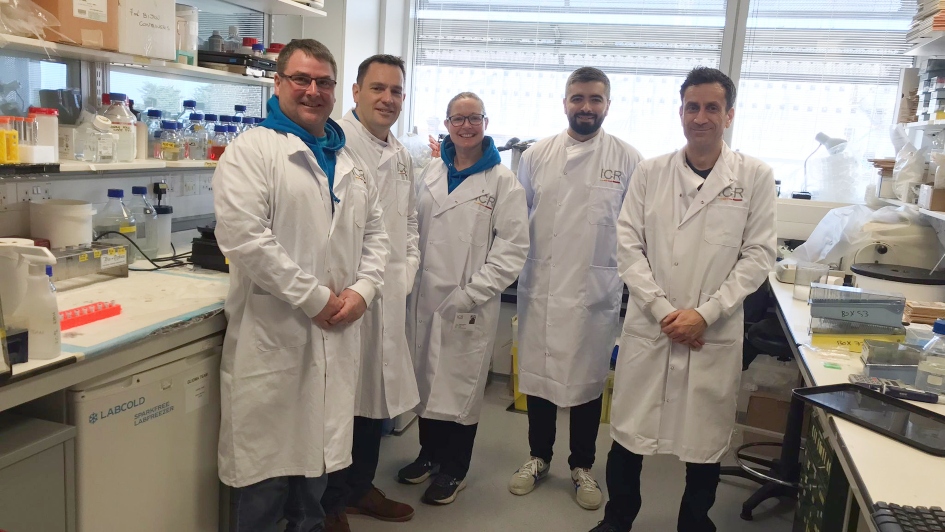

Image: From left to right, Simon, Stuart and Sarah from the Ollie Young Foundation visit Professor Chris Jones and Dr Yura Grabovska in their lab. Credit: The ICR.

‘We want other children to grow up and to get to be children’

Since we set up the Foundation, we’ve raised £170,000 to fund research at the ICR. We got to visit the labs for the first time this year – Covid had stopped us from visiting any earlier – and we got to meet Professor Chris Jones, and Dr Yura Grabovska, whose work we help fund.

Seeing the research that we’re supporting first-hand was really encouraging. It looks like a lot of progress has been made, and we’re looking forward to seeing what the future holds.

The aim of the Foundation is just to raise as much money as we can into the type of brain tumour Ollie had. I remember when leukaemia was at its infancy, and people didn’t know how to treat it. But down the line, with a lot of funding, and a lot of research behind it, treatments have been developed, and more and more people are surviving.

There’s a lot of hope, and I think the future is bright, but I also think it’s really important that we don’t stop. We have to keep moving forwards, because we want to help other families, and we would like other children to be able to grow up and to get to be children.

Donate to the Ollie Young Foundation

We are world-leaders in the study of cancer in children, teenagers and young adults. Our international research efforts are key in transforming how childhood cancers are treated.

Find out more about our Family Charity Partners, whose support and dedication drives our work forward.

Find out more

comments powered by