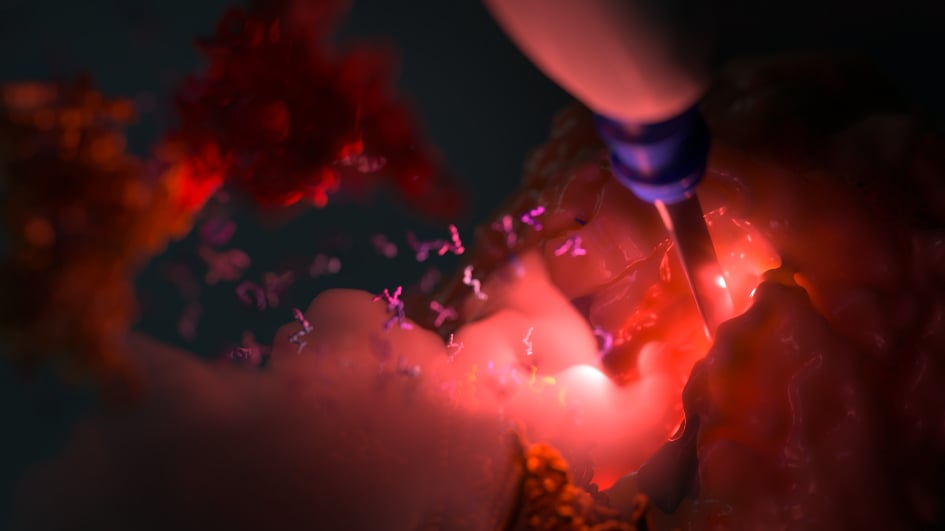

Image: iKnife cutting into a tumour. Credit: Jeroen Claus, Phospho Biomedical Animation

It’s no secret that what we eat and drink can affect how certain medical treatments work.

You may have heard that we should avoid taking ibuprofen on an empty stomach and that grapefruit juice can interfere with medicines like statins and antihistamines.

There has been some evidence that diet could play an important role in responses to cancer treatments too.

For example, a few years ago, a group of researchers found that some cancer cells depend on the amino acid asparagine to grow and spread, and that limiting it in the diet could stop cancer from spreading in mice with breast cancer.

On top of that, a different team found that excess amounts of another amino acid – histidine – makes leukaemia cells in mice more sensitive to the chemotherapy drug methotrexate.

However, a new study published yesterday goes a step further and suggests that eating the right foods – or in this case, avoiding the wrong ones – can tweak a tumour's metabolism to make it vulnerable to treatment.

The study, carried out in mice and published in Cell, is one of the first to show that by avoiding certain foods we can make an otherwise useless treatment effective against cancer. In other words, it’s not just that diet makes the treatment more effective – it ensures it works.

Depriving cancer cells of necessary nutrients

The study, led by Dr George Poulogiannis and his colleagues at the ICR, looks at a new class of drug known as cPLA2 inhibitors, which are used in clinical trials to treat inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis or dermatitis – and are now being considered for trialling in cancer. The drug can target a key molecule known as cPLA2 and directly influence cancer's energy supply in mice.

Cancer cells use certain metabolic pathways to break down and obtain nutrients in ways that support their uncontrolled growth and spread. These pathways are often seen as a potential weakness that we can take advantage of. How? For example, by using a drug that blocks the pathway, which would deprive cancer cells of necessary nutrients.

Dr Poulogiannis, leader of the Signalling and Cancer Metabolism team behind the research at the ICR said, “It takes a lot for cancer cells to divide as often and spread as much as they do. They need lots of fuel.”

In this new study, researchers found that cancers with mutations in the PI3K signalling pathway – which has been linked to almost all human cancers – rely on omega-6 fats to grow and spread.

The molecule cPLA2 in PI3K-mutant cancer cells releases arachidonic acid – a type of omega-6 fatty acid – that fuels the cancer and allows it to keep growing.

Dr Poulogiannis explained:

“We believe that when cancers acquire mutations in genes that are part of the PI3K signalling pathway – a key signalling pathway promoting many key functions such as cell survival and growth – cancer cells are able to take advantage of this pathway and become more reliant on certain fat to sustain their rapid growth and proliferation.”

Meat and dairy products are major sources of arachidonic acid. However, other omega-6 fatty acids such as linoleic acid, which can be found in sunflower oil, can also be converted by the body into arachidonic acid. This means that there are many different ways in which this cancer can obtain the fuel it needs to grow – it can release it, or it can use the arachidonic acid from foods we consume.

Eliminating omega-6 fats from the diet

Researchers used cPLA2 inhibitor drugs in mice to block the cPLA2 molecule from releasing arachidonic acid. However, because Western diets contain high amounts of omega-6 fats, researchers also had to feed mice a diet free from processed meat, dairy and processed vegetable oils. These are all foods high in omega-6 fatty acids, and by eliminating them from the diet, researchers enabled cPLA2 inhibitor drugs to work effectively against cancer in mice.

“By getting rid of all the fat that sustains cancer’s growth – through combining an experimental drug and diet changes – we can defeat cancer in mice by targeting its metabolism,” explained Dr Poulogiannis.

These findings open up the possibility of running new clinical trials where diet plays a key role and suggest that avoiding certain foods in combination with a targeted cancer drug could help attack tumours’ metabolism in future treatment strategies.

However, these findings do not mean that every cancer patient would benefit from a fat-free diet – and they do not have any impact on existing, approved cancer treatments. After all, fat is one of the three main macronutrients that we need to survive, and completely cutting it out from our diet for no reason would not be healthy.

What next for this research?

If the findings are successfully translated into humans through a clinical trial which is currently being planned, the approach could be relevant to many different cancer types with mutations in the PI3K pathway.

And Dr Poulogiannis believes the principles established in this study could mean that, when it comes to cancer, in the not-too-distant future, what we eat could have a much bigger role in how we treat.

He concludes: “As we are able to unravel new evidence and understand more about the metabolism of cancer cells, using diet and nutrition to complement targeted drugs gets closer to becoming a reality.”

comments powered by