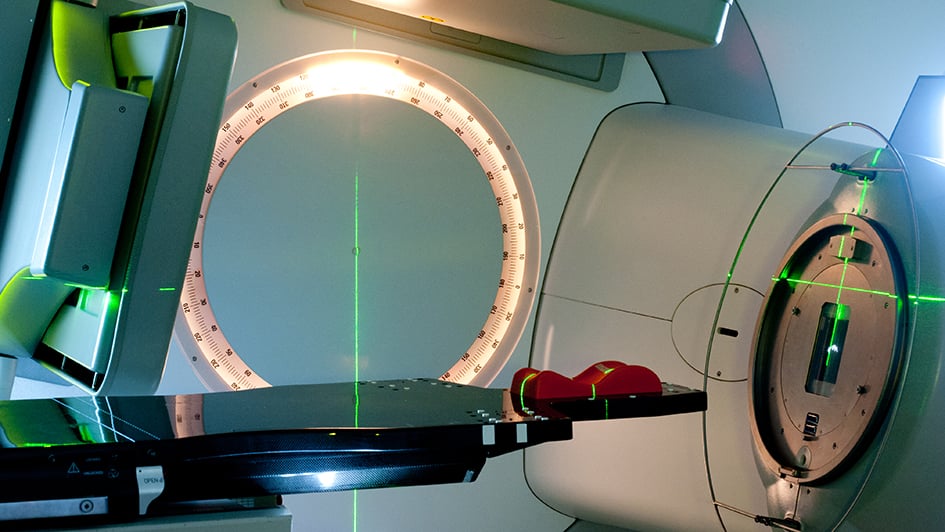

Radiotherapy machine at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust (photo: Jan Chlebik/the ICR)

Treating bladder and head-and-neck cancers with an experimental drug called CCT244747 makes radiotherapy more successful at killing them, scientists have discovered.

The research could pave the way for more effective treatment for these diseases.

A new study led by Professor Kevin Harrington and Dr Shane Zaidi of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, showed that pre-treating cancerous cells with the compound led to more cells dying following radiotherapy.

The drug also significantly slowed the growth of human cancer tumours grown in mice. After 70 days, mice treated with both CCT244747 and radiotherapy had tumours around half the size of those in mice that had only been treated with radiotherapy.

Damage limitation

CCT244747 is a type of molecule called a Chk1 inhibitor. It was discovered by scientists at the ICR, in collaboration with cancer drug discovery company Sareum.

The Chk1 inhibitor program was subsequently licensed to the Cancer Research Technology Pioneer Fund and then sub-licensed to Sierra Oncology (formerly ProNAi Therapeutics).

Sierra Oncology is actively pursuing a broad clinical development program at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, employing an analogue of CCT244747 known as SRA737.

Chk1 inhibitors stop cells from entering a ‘rest and repair’ state if they detect DNA mutations – a key survival mechanism for cancerous cells after radiotherapy.

In the new study, published in the journal Radiotherapy and Oncology, cells from bladder and head and neck tumours were irradiated after treatment with CCT244747.

The cells continued to try to grow and divide despite the damage. As a result, they either died prematurely, or passed on irreparable mutations to their descendants.

A new treatment option?

The researchers also found that the inhibitor only had this effect on cancerous cells. When they combined CCT244747 and radiotherapy treatment for healthy cells, the treatment was no more damaging than radiotherapy alone.

The research was funded by a range of organisations including Cancer Research UK, the Oracle Cancer Trust, the Rosetrees Trust and the Anthony Long Trust.

Study co-leader Professor Harrington, Joint Head of the Division of Radiotherapy and Imaging at the ICR, said: “Our study has shown that an experimental Chk1 inhibitor effectively sensitises cancer cells grown in the lab and in mice to radiotherapy treatment – and could in the future become a new and effective treatment option in bladder and head and neck cancer.”