-embed.jpg?sfvrsn=ccb27b69_0)

Dispensing medicines for a clinical trial (photo: Jan Chlebik/the ICR)

Our understanding of some childhood cancers has been revolutionised by recent research — including studies here at The Institute of Cancer Research, London — which showed that, at the molecular level, tumours that emerge in childhood are not the same cancers as those diagnosed later in life.

But if these essential new understandings of cancer biology are to be turned into new treatments, clinical trials need to modernise in order to keep in step.

This was the theme of a summit last year in San Francisco, US, where Professor Chris Jones, leader of the ICR’s Glioma Team, represented the institute.

An official report of that meeting, which brought together experts from across the world, was published this month in the journal Neuro-Oncology, and looks forward with hope to a future where children will benefit from a new generation of ‘smarter’ clinical trials.

The delegates in San Francisco, who were experts in aggressive, high-grade brain cancers, had gathered to discuss the new challenges in designing laboratory and clinical studies in an era when high-grade gliomas of childhood — a common brain cancer type — are now known to be so different from adult gliomas as to need a different approach to treatment.

Lack of progress

As Professor Jones lays out in the new report, the failure to find any new and more effective treatments for high-grade gliomas in children has been partly because of a lack of understanding of their biology. There have been no significant improvements in survival for these cancers in decades.

In the past, children with untreatable cancers like diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), which claims the life of every child who develops it in an average of 9-12 months, have been offered treatments that hold hope for adult glioma.

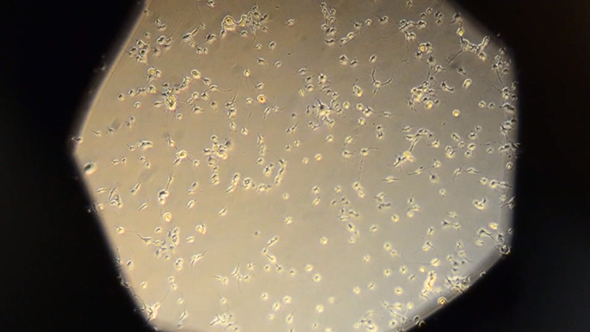

DIPG cells under the microscope

These treatments haven’t worked. Most studies of these treatments have shown that they lead to side-effects — which can be particularly severe in children — without bringing any benefit.

As Professor Jones writes in the report: “Funders, regulatory agencies, pharma, and clinicians have to work together to develop strategies that limit unnecessary risk but also offer reasonable hope to these patients. They cannot be ignored simply because they are children and/or because their tumours are rare.”

Hope for the future

So how do we bring more hope to children and their families who are affected by aggressive brain cancers?

The answer lies in research collaboration, careful and rational design of clinical trials, and greater biological understanding of brain cancers in children.

Researchers can only prove the effectiveness of a treatment for a cancer like DIPG by trialling it in more children than are actually diagnosed each year in the UK, so international collaborations between researchers are vital to run trials in enough children.

These collaborations are already being formed — through meetings like the San Francisco conference, and through research studies that depend on the expertise of different groups across the globe.

For example, a recent study led by Professor Jones not only provided a crucial new insight into DIPG, but also showed the importance of taking biopsies from children with the disease in order to make new discoveries. This is currently not done routinely in the UK, but thanks to a group of researchers in Paris, France, Professor Jones was able to discover a possible drug target for DIPG.

Inspiring time for researchers

Researchers also need to be clever in how they design trials, taking possible opportunities to classify cancers by molecular subtype rather than based on where they grow.

There are signs that some DIPGs share genetic characteristics with other forms of high-grade glioma and could be targeted by the same treatments, so children with either type could be enrolled together on a future trial.

And some genetic mutations are rare in children but more common in adult gliomas — so the needs of these children could be best served by enrolling on a separate arm of an adult trial.

It’s an inspiring time for researchers in rare childhood cancers as a wave of scientific discoveries offer up new clues about what kinds of treatment could be effective, and how trials could be run.

Researchers like Professor Jones — with the support of families like those of Abbie Mifsud, who lost her fight with DIPG aged six, and whose family founded the charity Abbie’s Army to fund research into the disease — are determined to build on these new discoveries to improve survival in rare childhood cancers.

comments powered by